Ever since the Harry Ransom Center acquired the papers of David Foster Wallace and started posting photos of his annotated books, there has been a great deal of fuss about them. I think I even posted a few images myself on my Tumblr and/or here. People really started going into rhapsodies when someone posted what he said was DFW’s copy of Ulysses — though eventually he revealed that it was just a prank.

DFW has become something like a patron saint of close reading, and who knows how many young writers and would-be writers out there have started writing copiously in their books in imitatio Davei? It’s hard to regret this, since careful, attentive reading is a pretty cool thing to be the patron saint of. And even if people start annotating just to be like DFW rather than to understand their books better, chances are that the practice will indeed help them as readers if they stick with it. Fake it ‘till you make it, as the wise men say.

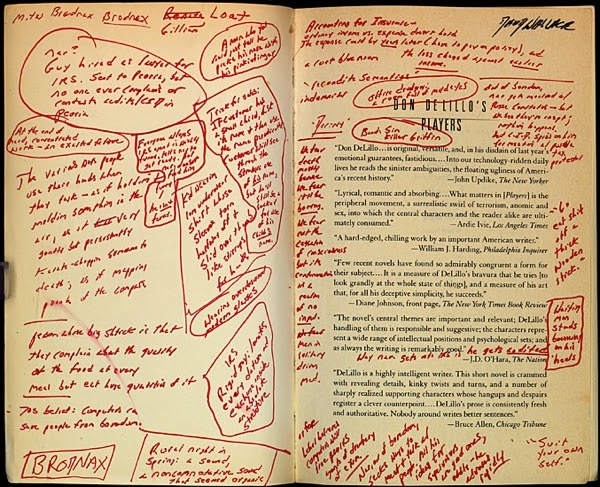

Mike Miley has been working in the DFW archives, and has found it a somewhat harrowing experience, in two ways. First, there is DFW’s habit of reading everything as a commentary on his own struggles and pathologies:

Critics and fans alike rhapsodize about identifying with David Foster Wallace’s writing as though it can only be consoling and empowering, and I used to think so too, until I got too close and discovered what may be the most important truth about literature, the true “aesthetic benefit of close reading,” though I doubt the Mellon Foundation would be all that interested in hearing about my discovery, as it is beneficial only in the most cautionary of senses: there is such a thing as reading too closely.

Wallace’s annotations suggest that he had been reading too closely, searching for too much validation, guidance, or comfort in the books he read, to the point that his reading only wound up reinforcing his worst tendencies. Wallace found no escape from himself while he was reading; rather, his personal library remained just that: personal, continually bringing him back to his own struggles and inadequacies.

But there is also the danger, the greater danger, that the devoted fan will imitate DFW not just in his moral earnestness and intellectual rigor, but in that very self-absorption:

And I found myself in danger of following him. Yes, this begins and ends as being about me, the guy in the frosty reading room in Austin, for fandom is always about the fan; the self is always the subject. The artist is, at best, the mask fans wear to distract themselves from the fact that they are looking into a mirror. I learned far more about myself through reading Wallace reading than I learned about David Foster Wallace. I discovered I had been reading Wallace too closely. For years I looked to Wallace for answers to just about everything — how to think, how to live, what to read and how. Turns out, I got what I wanted, if what I wanted was a more erudite way to criticize myself or a higher, more crippling level of self-consciousness than I already had. I did wind up understanding myself better, if only to understand where I might be headed and what I must avoid becoming.

This is why I’ve taken over two years to finish writing this, why I’ve stalled out time and time again in search of the right voice or style or insight into something that feels both too large for me to take on and too close for me to see clearly. This “DFW” persona, this mental state of Wallace’s, was a reflection of mine as well, albeit distorted and exaggerated through a funhouse mirror darkly. Wallace’s work reads like a more articulate, insightful version of the ticker-tape running in our own skulls — this is the cliché that everyone employs to describe Wallace’s writing, and for me it is absolutely true. However, no one really interrogates what that statement means or how far something like that goes. If I keep reading Wallace this closely, will I end up resembling him even more closely? Do the devices I borrow from him here — self-aware reportage, direct interrogation, hyperbolic jokes about mundane locations — show that I have moved beyond him or simply fallen further under his influence? If I continue on this path of emulation, will I reach the same conclusions about being alive as he did?

Miley’s essay is a sobering one, and you get the sense that he reached this level of genuine self-awareness (as opposed to mere self-absorption) just in time.

I don’t think I’ve seen, in my lifetime, a writer who has generated the kind and intensity of veneration that DFW has. We might contrast his fans to, say, Tolkien fans, who know a little bit about the author — enough to have an image of a man in a colorful waistcoat smoking a pipe — but who can’t spare much time for him because they are so fully absorbed in his legendarium. But the people I know who love every word of Infinite Jest are also fascinated by Wallace himself: they are constantly aware of him as its author, of its relations to the circumstances of his own life.

Montaigne said of his Essays that “It is a book consubstantial with its author,” and this seems to be true for everything DFW wrote. Absorption in his work seems almost necessarily to involve scrutiny of his life. And given how his life ended, it’s hard not to see this as a worrisome trend. What I wouldn’t give for a detailed and sensitive ethnography of DFW devotees — something like what Tanya Luhrmann did for charismatic evangelicals.

> For years I looked to Wallace for answers to just about everything — how to think, how to live, what to read and how.

Well that’s just silly. He was a writer, not a guru. Certainly he (Wallace) would have been intensely uncomfortable with someone looking to him for instructions on “how to live”.

Anyway — much of Wallace’s work indicts exactly the hyper-anxious self-obsession Miley is talking about. If reading Wallace sends him tumbling into self-absorption, he’s mimicking Wallace’s affliction instead of listening to what he has to say about it (which is: it’s terrible).

I almost didn't approve that comment on the grounds of uncharitableness. Miley is confessing that he shouldn't have elevated DFW so high; there's no need to pile on by calling him "silly."

The interesting general point is this: many people treat writers as gurus. It's not just DFW, though his celebrants seem to be particularly intense. So why is this? How did literary writers come to be venerated as sages, including writers who never wanted to be seen in that light? (I'm actually writing about this, thus my curiosity. Hint: it really starts in the Victorian era.)

Fair enough.

I think this attraction to writer-as-sage and DFW in particular also has to do with the 'scourge of relatability' discussed in an earlier post. If relatability truly is considered to be the highest virtue of a text by many readers today, it makes sense why DFW is so venerated–he is supremely, addictively relatable.

To your general 'why is this' question, might it be something like writers (and scientists and philosophers and other meaning-makers) stepping into (and being thrust into) a priestly role in the wake of the disenchantment of the world? Not to mention that this view of the writer was actively encouraged by those incorrigible romantics, unacknowledged legislators all.