|

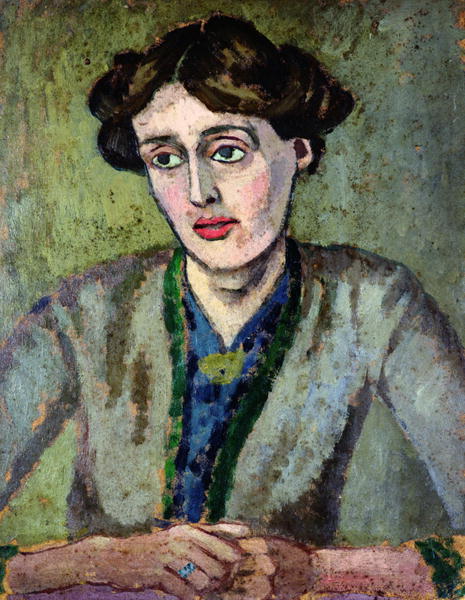

| Portrait of Virginia Woolf by Roger Fry (Wikimedia) |

Suzanne Berne on Virginia Woolf: A Portrait, by Viviane Forrester:

But it’s Leonard who gets dragged in front of the firing squad. Not only did he encourage Bell’s patronizing portrayal of Virginia; according to Forrester, he was also responsible for his wife’s only true psychotic episode, and probably helped usher her toward suicide. These accusations are fierce and emphatic: Leonard projected his own neuroses and his own frigidity onto Woolf (he had a horror of beginner sex and found most women’s bodies “extraordinarily ugly”). He married her strictly to get out of Ceylon, where he was in the British Foreign Service and where he had fallen into a suicidal depression. (He hated both the place and the position, though he pretended later to have thrown over a fabulous career for Virginia.) Without medical corroboration, he decreed that she was too unbalanced to have children, triggering her legendary mental breakdown immediately after their honeymoon. Then he held the threat of institutionalization over her, coercing her into a secluded country lifestyle that suited him but isolated and disheartened her, while using his marriage as entrée to an aristocratic, intellectual world that, as “a penniless Jew” from the professional class — just barely out of a shopkeeper’s apron — he could not have otherwise hoped to join.

This excerpt from Forrester’s book confirms Berne’s description of Forrester’s attack on Leonard Woolf.

When, in March of 1941, Woolf decided to take her own life, here is the heart-wrenching letter she left for Leonard:

Dearest,

I feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that – everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer.

I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been.

Forrester quotes that last line in her book (p. 203) and offers one line of commentary on it: “What was Virginia Woolf denied? Respect.”

What counts as denying someone respect? Offhand, I’d say that if I believed that I understood the emotional life and intimate relationships of a great artist I had never met, and who died before I came of age, better than she understood them herself … that would be denying her respect.

Among other things, Forrester demonstrates a total misunderstanding of the nature of clinical depression here.

I think that's exactly right, Freddie — while Woolf's heartbreaking letter is a brilliant demonstration of just how clearly the profoundly depressed can see their own lives and the lives of those they love. People who think that depression "blinds you to reality" have never been seriously depressed or lived with a seriously depressed person. The acuity of insight that depressed people can have is a terrifying thing.

yes