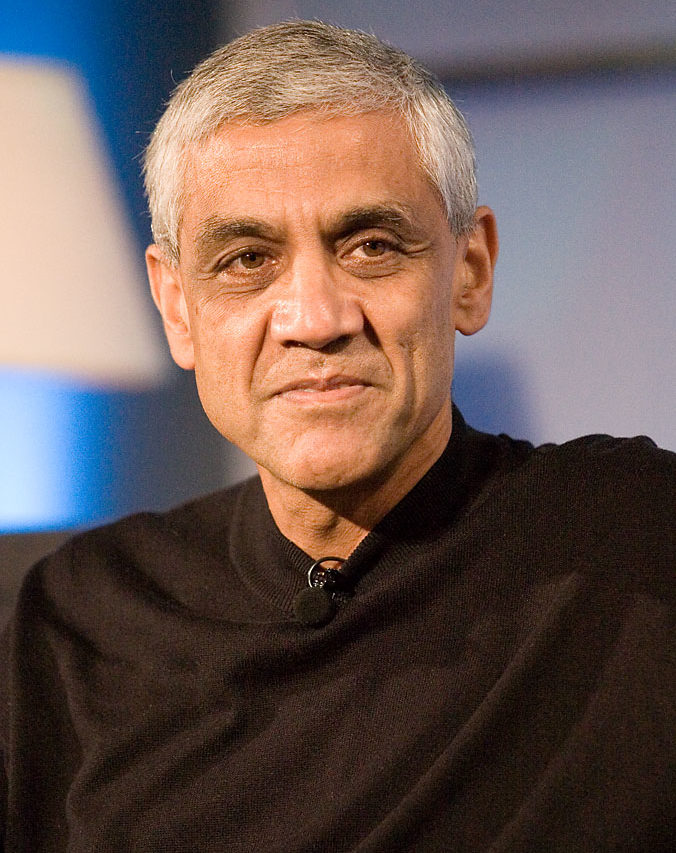

In 2012, at the Health Innovation Summit in San Francisco, Vinod Khosla, Sun Microsystems co-founder and venture capitalist, declared: “Health care is like witchcraft and just based on tradition.” Biased and fallible physicians, he continued, don’t use enough science or data — and thus machines will someday rightly replace 80 percent of doctors. Earlier that same year, Khosla had penned an article for TechCrunch in which he had made a similar point. With the capacity to store and analyze every single biological detail, computers would soon outperform human doctors. He writes, “there are three thousand or more metabolic pathways, I was once told, in the human body and they impact each other in very complex ways. These tasks are perfect for a computer to model as ‘systems biology’ researchers are trying to do.” In Khosla’s vision of the future, by around 2022 he expects he will “be able to ask Siri’s great great grandchild (Version 9.0?) for an opinion far more accurate than the one I get today from the average physician.” In May 2014, Khosla reiterated his assertion that computers will replace most doctors. “Humans are not good when 500 variables affect a disease. We can handle three to five to seven, maybe,” he said. “We are guided too much by opinions, not by statistical science.”

In 2012, at the Health Innovation Summit in San Francisco, Vinod Khosla, Sun Microsystems co-founder and venture capitalist, declared: “Health care is like witchcraft and just based on tradition.” Biased and fallible physicians, he continued, don’t use enough science or data — and thus machines will someday rightly replace 80 percent of doctors. Earlier that same year, Khosla had penned an article for TechCrunch in which he had made a similar point. With the capacity to store and analyze every single biological detail, computers would soon outperform human doctors. He writes, “there are three thousand or more metabolic pathways, I was once told, in the human body and they impact each other in very complex ways. These tasks are perfect for a computer to model as ‘systems biology’ researchers are trying to do.” In Khosla’s vision of the future, by around 2022 he expects he will “be able to ask Siri’s great great grandchild (Version 9.0?) for an opinion far more accurate than the one I get today from the average physician.” In May 2014, Khosla reiterated his assertion that computers will replace most doctors. “Humans are not good when 500 variables affect a disease. We can handle three to five to seven, maybe,” he said. “We are guided too much by opinions, not by statistical science.”

The dream of replacing doctors with advanced artificial intelligence is unsurprising, as talk of robots replacing human workers in various fields — from eldercare to taxi driving — has become common. But is Vinod Khosla right about medicine? Will we soon walk into clinics and be seen by robot diagnosticians who will cull our health information, evaluate our symptoms, and prescribe a treatment? Whether or not the technology will exist is difficult to predict, but we are certainly on our way there. The IBM supercomputer Watson is already being used in some hospitals to help diagnose cancer and recommend treatment, which it does by sifting through millions of patient records and producing treatment options based on previous outcomes. Analysts at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center are training Watson “to extract and interpret physician notes, lab results, and clinical research.” All this is awe-inspiring. Let us generously assume, then, for a moment, that the technology for Khosla’s future will be available and that all knowledge about and treatment options for medical problems will be readily analyzable by a computer within the next decade or so. If this is the future, why shouldn’t physicians be replaced?

There are several errors in Khosla’s way of thinking about this issue. First of all, modern health care is not “like witchcraft.” Academic physicians, for example, use evidence-based medicine whenever it is available. And when it isn’t, then they try to reason through a problem using what biologists know about disease presentation, physiology, and pharmacology.

Moreover, Khosla mischaracterizes the doctor-patient interaction. For Khosla, a visit to the doctor involves “friendly banter” and questions about symptoms. The doctor then assesses these symptoms, “hunts around … for clues as to their source, provides the diagnosis, writes a prescription, and sends you off.” In Khosla’s estimation the entire visit “should take no more than 15 minutes and usually takes probably less than that.” But the kind of visit Khosla writes about is an urgent care visit wherein quick and minor issues are addressed: strep throat or a small laceration requiring a stitch or two. Yes, these visits can take fifteen minutes, but so much of medicine does not involve these brief interactions. Consider the diabetic patient who has poorly controlled blood sugars, putting her at risk for stroke, heart attack, peripheral nerve destruction, and kidney failure, but who hasn’t been taking her medications. Or consider a patient addicted to cigarettes or on the verge of alcoholism. Consider the patient with Parkinson’s disease who wonders how this new diagnosis will affect his life. And what about the worried parents who want antibiotics for their child even though their child has a viral infection and not a bacterial infection? I can go on and on with scenarios like these, which occur hourly, if not daily, in nearly every medical specialty. In fact, fifteen-minute visits are the exception to the kind of medicine most physicians need to practice. One cannot convince an alcoholic to give up alcohol, get a diabetic patient to take her medications, or teach a Spanish-speaking patient to take his pills correctly in fifteen minutes. In addition, all this is impossible without “friendly banter.”

As Dr. Danielle Ofri, an associate professor of medicine at the New York University School of Medicine,

wrote in a New York Times blog post, compliance with blood pressure medications or diabetic medications is extremely difficult, involving multiple factors:

Besides obtaining five prescriptions and getting to the pharmacy to fill them (and that’s assuming no hassles with the insurance company, and that the patient actually has insurance), the patient would also be expected to cut down on salt and fat at each meal, exercise three or four times per week, make it to doctors’ appointments, get blood tests before each appointment, check blood sugar, get flu shots — on top of remembering to take the morning pills and then the evening pills each and every day.

Added up, that’s more than 3,000 behaviors to attend to, each year, to be truly adherent to all of the doctor’s recommendations.

Because of the difficulties involved in getting a patient to comply with a complex treatment plan, Dr. John Steiner argues in an article in the Annals of Internal Medicine that in order to be effective we must address individual, social, and environmental factors:

Counseling with a trusted clinician needs to be complemented by outreach interventions and removal of structural and organizational barriers. …[F]ront-line clinicians, interdisciplinary teams, organizational leaders, and policymakers will need to coordinate efforts in ways that exemplify the underlying principles of health care reform.

Therefore, the interaction between physician and patient cannot be dispensed with in fifteen minutes. No, the relationship involves, at minimum, a negotiation between what the doctor thinks is right and what the patient is capable of and wants. To use the example of the diabetic patient, perhaps the first step is to get the patient to give up soda for water, which will help lower blood sugars, or to start walking instead of driving, or taking the stairs instead of the elevator. We make small suggestions and patients make small compromises in order to change for the better — a negotiation that helps patients improve in a way that is admittedly slow, but necessarily slow. This requires the kind of give-and-take that we naturally have in relationships with other people, but not with computers.

Khosla neglects other elements of medical care, too. Implicit in his comments is the idea that the patient is a consumer and the doctor a salesman. In this setting, the patient buys health in the same way that he or she buys corn on the cob. One doesn’t need friendly banter or a packet of paperwork to get the best corn, only a short visit to the grocery store.

And yet, issues of health are far more serious than buying produce. Let’s take the example of a mother who brings her child in for ADHD medication, a scenario I’ve seen multiple times. “My child has ADHD,” she says. “He needs Ritalin to help his symptoms.” In a consumer-provider scenario, the doctor gives the mother Ritalin. This is what she wants; she is paying for the visit; the customer is king. But someone must explain to the mother what ADHD is and whether her child actually has this disorder. There must be a conversation about the diagnosis, the medication, and its side effects, because the consequences of these are lifelong. Machines would have to be more than just clerks. In many instances, they would have to convince the parent that, perhaps, her child does not have ADHD; that she should hold off on medications and schedule a follow-up to see how the child is doing. Because the exchange of goods in medicine is so unique, consequential, and rife with emotion, it is not just a consumer-cashier relationship. Thus computers, no matter how efficient, are ill-fitted to this task.

Khosla also misunderstands certain treatments, which are directly based on human interactions. Take psychiatry for example. We know that cognitive behavioral therapy and medication combined are the best treatment for a disease like depression. And cognitive behavioral therapy has at its core the relationship between the psychiatrist or therapist and the patient, who together work through a depressed patient’s illness during therapy sessions. In cognitive behavioral therapy, private aspects of life are discussed and comfort is offered — human expressions and emotions are critical for this mode of treatment.

a PC with a neural network can diagnose better than MOST doctors

great