Imagine, for a moment, that your kidneys have failed. Perhaps you had longstanding, uncontrolled diabetes. Or, you might have had persistently high blood pressure (hypertension). You could not afford your medications, you refused to take them, or you never even visited your doctor and thus never knew you were sick. Whatever the reason, your kidneys no longer work.

|

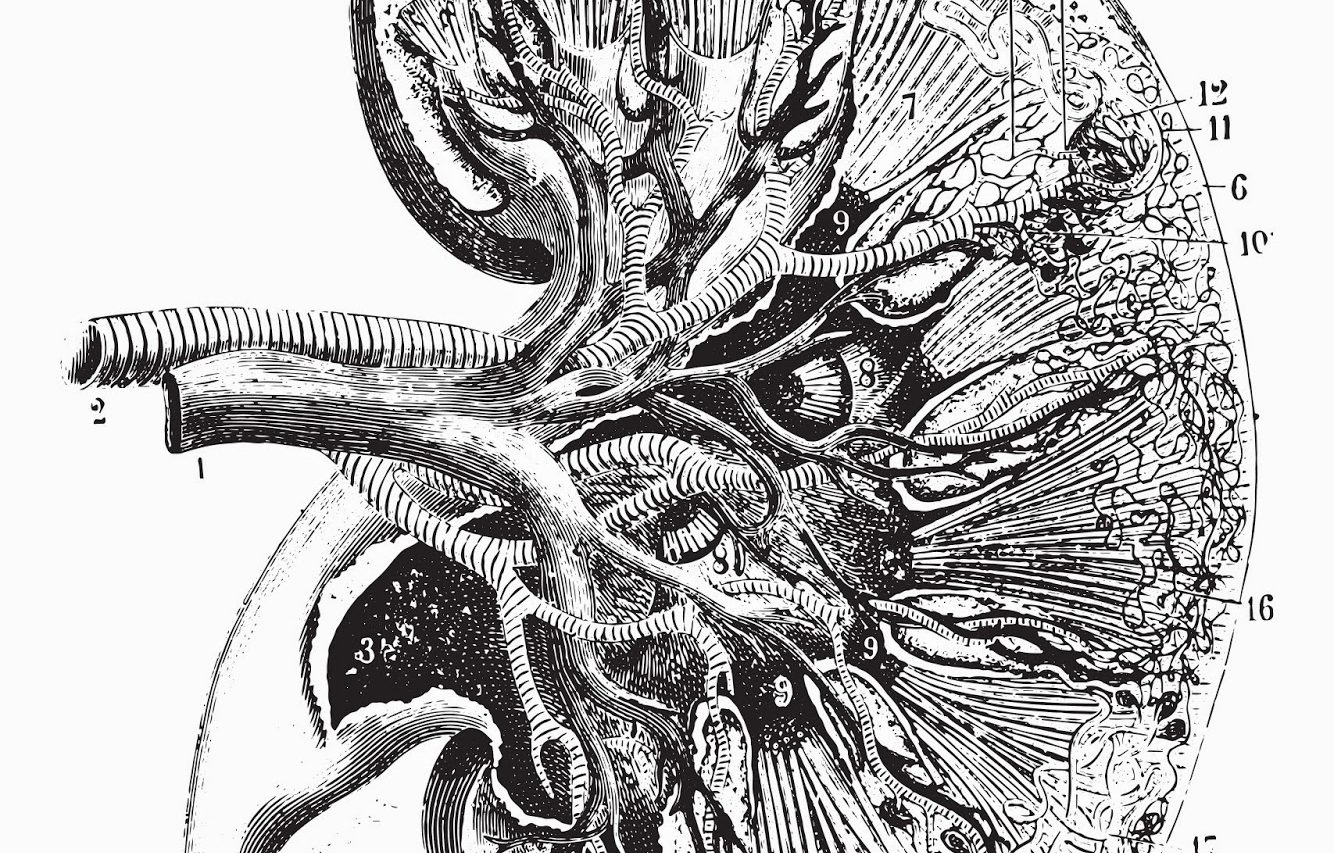

| Engraving of a section of a kidney, from a medical journal edited by Dr. Paul Labarthe in the 1880s. Image via Shutterstock |

But these two baseball-sized organs used to work so efficiently, even beautifully. They filtered out toxic compounds and electrolytes from the blood. These filtered-out, noxious materials then traveled through abundant yet minuscule tubes which were divided up into different parts like the Thick Ascending Limb and the Distal Convoluted Tubule. These tubes contained channels like Aquaporin and Sodium Potassium Chloride Cotransporter. In turn, the channels used various physical laws of concentration gradient, electrical charge, and chemical-bond energy and transported electrolytes and water into and out of this conglomerate of toxic compounds which eventually became urine. Amazingly, these small organs controlled your blood pressure, thirst, and hydration status — among many other vital aspects of life. The kidneys did this with such grace that you didn’t even know it was going on.

Now, however, your chronic disease has destroyed these organs. Proteins, which shouldn’t normally be in the urine, pour out of the body causing fluid buildup outside the vascular spaces. Proteins like albumin normally maintain fluid in the blood vessels by using osmotic pressure to draw fluid out of the extravascular spaces and into the vasculature. But when proteins disappear, this no longer occurs and fluid leaks out of blood vessels. Consequently, your legs and fingers swell with fluid, also known as edema. If your kidneys can’t even produce urine to excrete protein, edema still manifests. Without urine excretion, sodium and fluid accumulate in the blood and are eventually pushed out into the extravascular space.

Kidney failure affects electrolytes other than sodium as well. Potassium, for instance, is an electrolyte vital to muscle and heart function. But with kidney failure, your body retains too much potassium. With an excess of potassium (hyperkalemia), cardiac cells experience chaotic functioning potentially leading to cardiac arrest. Furthermore, your blood pressure, which depends on the kidney’s balance of electrolytes like sodium and chloride as well as hormones called aldosterone and renin (these involve the kidney in complex feedback loops) becomes higher and less malleable.

Other systemic effects include the inability of your infection-fighting cells to work as they ought to, a dysfunction of your body’s platelets which help to stop bleeding after you’ve cut yourself, seizures, shortness of breath, insomnia, inflammation around the heart, restless legs, muscle twitching, brittle bones, blurry vision, and death.

Is there a cure for this? What should you do now? You need a form of dialysis. If your kidneys can’t do all these things, a machine must do them for you. It sounds simple but it is no pleasant experience. First, the surgeons create an arteriovenous fistula in your arm so that the dialysis nurse can easily access your blood. The arteriovenous fistula directly connects an artery and vein mixing oxygenated and non-oxygenated blood. This is not flattering to the skin — the veins, because they now receive more blood flow, pop out and frequently look like blue worms squirming beneath the epidermis. Next, you must go to a dialysis center three times a week with dozens of other patients just like you.

|

| Image via Shutterstock |

After you check in at the dialysis center, you walk into a long and expansive room filled with chairs next to machines that stand nearly four feet tall. The machines look complex and, at once, amateur. There are wheels inside the machines which spin next to each other like the wheels that spin an audio tape or a video tape from the 1990s. Long, clear tubing comes out from the machine, splits into two prongs, and attaches to needles which enter your arteriovenous fistula.

As you walk into the room you see all the other patients sleeping in their reclining chairs or watching TV in silence; their arms lie out on the small tables attached to the dialysis machines, as if in some opium den. That creepy feeling you experience as you walk into this large room is understandable but you’ll habituate to it. In order to get started, simply sit in an empty chair next to a machine. Offer up your arm with the arteriovenous fistula to the nurse and relax as the machine does all the work.

Dialysis replicates the actions of the kidney. Inside the dialysis machine, a semipermeable membrane acts as a strainer with microscopic pores, allowing substances like water, sugar, electrolytes, and urea to exit as the rest of the blood, now without toxic substances, is pumped back into the body. This takes some time — around four hours — so take a book or multiple movies for entertainment. Oh, don’t forget about the potential complications that can occur during this time: low blood pressure, itching, muscle cramping, headache, chest pain, heart arrhythmias, and possible seizure or coma. If you miss multiple dialysis sessions, you may expire. So don’t vacation anywhere without a dialysis center. And you should probably put yourself on a kidney-transplant list — you can join the 100,602 others who are waiting for one . Or, if you have the money, perhaps you can buy a kidney on the international organ transplant market . If not though, it’s okay, because we can continue to give you dialysis.

Great piece; the dialysis room and vibe are exactly as you've described them!

Separately, perhaps a regulated market for kidneys could alleviate the ever-lengthening wait times for a kidney and the ordeal that is dialysis.

Thanks, Jenner!

The New Atlantis has published some very interesting and serious essays on that topic: http://44.239.21.170/publications/gifts-of-the-body

http://44.239.21.170/publications/the-case-for-kidney-markets

http://44.239.21.170/publications/biotechnology-and-the-spirit-of-capitalism

http://44.239.21.170/publications/is-the-body-property

On a personal note, I think both sides of the debate have something valuable to say and I'm torn about this particular issue.

-Aaron