Reactions to mental illnesses or disorders vary. (I wrote about some of them in a 2012 essay in the pages of The New Atlantis.) I’ve noticed, however, that some of the responses among physicians differ from their reactions to other medical pathologies. There are several reasons why this might be the case, having to do with the fact that psychiatric pathology is far more difficult to comprehend and thus more easily misunderstood than the pathology of other diseases we usually associate only with the body, such as cancer or pneumonia.

|

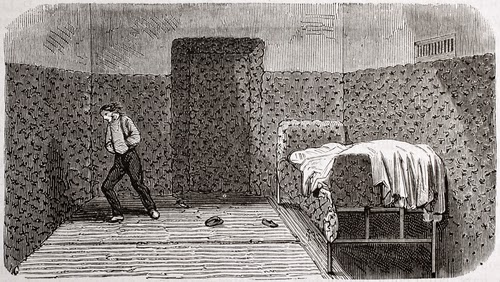

| Image via Shutterstock |

Unlike bodily illnesses, mental disorders primarily affect patients’ emotions and actions. As a consequence, our implicitly held beliefs about human behavior, especially our views of free will, can color how we react to people suffering from mental illness. A strong belief in free will helps validate a sense of justice and morality: generally speaking, people choose their actions and are thus responsible for them. So if a person with a psychiatric diagnosis commits suicide, kills another person, or runs onto a highway screaming at imaginary beings, it is easiest to hold the person morally responsible if we believe he acted freely. Or, in the case of suicide, we might say that the person “should have done” this or that to make life better: he should have seen a psychiatrist, or he should have realized how wonderful his life was. We want to hold the person responsible for his actions rather than deal with an illness that so often makes people completely irrational and incapable of choosing their actions.

Additionally, the fact that most medical pathology is visible to us makes it simpler to understand. In the emergency room we easily see the effects of a chopped-off leg. We can feel a large spleen, hear an irregular heartbeat, or view an abnormal lab finding. Psychiatric pathology, however, is not palpable in the same way. With schizophrenic patients, for example, we cannot see the beings they see. We do not inhabit the world they inhabit. Nor can we easily visualize their brain chemistry. It is as if we are looking for the culprit in a pitch-black world.

With these difficulties in understanding psychiatric disease, some physicians, patients and observers dismiss mental illness as a product of the weak-willed or obstreperous. Or they romanticize it, focusing on the interesting and provocative aspects of mental illness. These are minority views, but they are not without influence — which is unfortunate, because if they are followed, they can lead us to deny treatment to those who need it.

Dr. Robert Youngson, a British doctor-turned-author, is an instructive example of someone espousing dangerous views of this sort. In his 1999 book, The Madness of Prince Hamlet and Other Extraordinary States of Mind, he writes:

Doctors and lay people talk, quite casually, of ‘mental illness,’ the implication being that conditions like schizophrenia are much the same as conditions like tuberculosis or meningitis. In fact, they are not. Mental disorders have hardly anything in common with organic physical disease…. The observable changes occurring in the body — including the brain — in the course of organic disease are called pathology. So far as current research can demonstrate, there are no corresponding organic changes causing schizophrenia.

Dr. Youngson goes on to assert that we classify schizophrenia as an illness in order to maintain a society of “normal” people. He claims that British psychiatrists “carry out a tidying-up function much more closely equated with that of the police and the judiciary than with that of the medical profession.” Then he asks, disturbingly, whether there is “really any difference between what happened in Russia, when political dissidents were deemed to be mad and were incarcerated in mental hospitals, and what happens in Britain and America when people who do not conform to current social mores are legally certified and locked up.”

For support of his position, Dr. Youngson refers the reader to the work of the late Thomas Szasz, who, as a professor of psychiatry at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University at Syracuse, New York, published a number of controversial books arguing that mental illness is a myth. The status quo of medical practice that considers mental conditions like schizophrenia as illnesses, Dr. Youngson writes, is a “convenient fiction about a state of the mind.” (A critical essay about Dr. Szasz appeared in The New Atlantis in 2006.)

But Dr. Youngson’s premise, that schizophrenic patients lack cerebral pathology, is wrong. We know, for example, that patients with schizophrenia have a disruption in certain neurotransmitters in their brains. Dopamine is increased in patients with schizophrenia, and this possibly relates to the effects of genetic alterations. There are specific (and multiple) gene variants associated with this disease. Furthermore, medications do sometimes work, as I explained in another recent post. They inhibit dopamine’s actions on certain receptors in the brain and, despite their side effects, can rid patients of awful and belligerent visions and voices. If there were truly no pathology, why would blocking receptors work? If there were truly no pathology, why would there be significant elevations of certain neurotransmitters? There is indeed pathology here — Youngson apparently just chooses to ignore it because it contradicts his preferred explanations.

Dr. Paul McHugh, a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, wrote about this particular topic in a 1995 issue of The American Scholar. He argues that “the context of a life should not be confused with the cause of all mental disorders or made the sole focus of therapeutic attention as though guidance were always synonymous with cure.” Unfortunately, “the assumption that something must have happened if a mental disorder is present has provided an entry for zealots and charlatans into psychiatry.” If we believe that mental disorders like schizophrenia or depression are always rooted in life experiences and never in physical pathology, we can easily misunderstand patients, their families, and the possibilities for therapies. Not only is Dr. Youngson’s view wrong; it is injurious to those whom it is meant to help.

Dr. McHugh also addresses the romanticization of depression in a 2005 Commentary essay (which I quoted in another recent post). McHugh reviews Andrew Solomon’s book The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression (2001), in which Solomon writes about his own experiences with depression. Solomon, McHugh argues, romanticizes depression by making it seem mysterious like sex and curable most effectively by a sheer act of will. Similar to Dr. Youngson, Solomon mischaracterizes a terrible sickness. As McHugh writes,

the particular disorder at issue here is a disease, an affliction that disrupts a natural function of emotional control. This disease, like other diseases both physical and mental, renders the afflicted person impaired in ways that are essentially the same from case to case…. [Depression] is not a you but an it, a thing unto itself and not just the dark side of human emotion.

Again, depression, like schizophrenia, clearly involves pathologies in the brain. It is a real disease that tears apart human lives.

What’s so striking about these cases is that those who are denying or romanticizing mental illnesses are familiar with the diseases. Surely, Dr. Youngson saw schizophrenics in his family practice. Solomon experienced depression himself. And Dr. Szasz also saw patients with these disorders. Seeing or experiencing the illness, then, is not enough to understand it. An understanding of disorders of the mind requires that we not only learn about symptoms, social context, and pharmacology, but also that we understand the underlying pathology.

Actually, Szasz was right. A book that every doctor should read as soon as possible is Robert Whitaker's "Psychiatry Under the Influence." http://www.amazon.com/Psychiatry-Under-Influence-Institutional-Prescriptions/dp/1137506946