So wrote R. P. Blackmur, an eminent poet and critic from Princeton University, writing in the Sewanee Review in 1945. His essay is called “The Economy of the American Writer: Preliminary Notes,” and his chief question is whether it is possible for literary writers to make a living. Plus ça change, oui? An essay very much worth reading for anyone, but especially for people who think that the problem of the aspiring-artist-piecing-together-a-rough-living is a phenomenon of the millennial generation.

Anyhow, Blackmur is concerned because he has run some numbers.

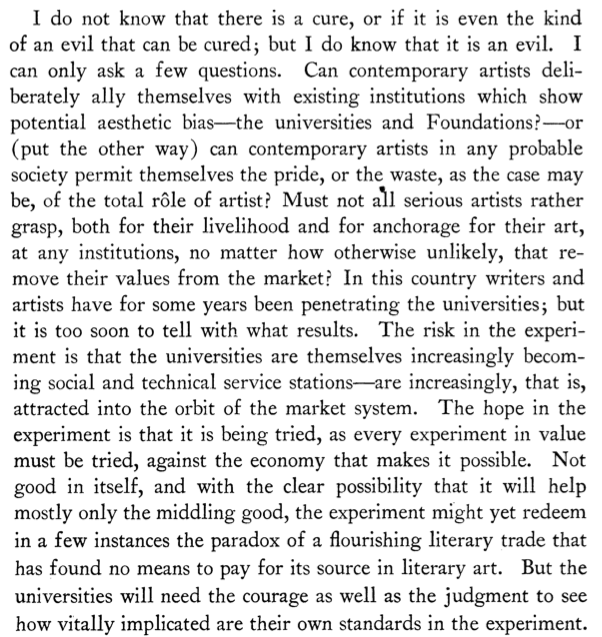

In these circumstances, where can the necessary money — money sufficient to allow artists to pursue their art full-time (or nearly so) — come from?

From our vantage point, perhaps the most interesting point here is Blackmur’s uncertainty about the most likely source of support for artists: will they find their place in the world of the university, or in the world of the non-profit foundation? We know how it turned out: while foundations do still support artists of various kinds, universities have turned out to be the chief patrons of American artists — especially writers.

Blackmur sees that even at his moment support for writers and artists is drifting towards the university; he’s just not altogether happy about that. He’s not happy because he has seen that “the universities are themselves increasingly becoming social and technical service stations — are increasingly attracted into the orbit of the market system.” Social and technical service stations: a prophetic word if there ever was one. The universities have in the intervening seventy years become generous patrons of the arts; but what is virtually impossible for us to see, because we can’t re-run history, is the extent to which the arts have been limited and confined by being absorbed into an institution that has utterly lost its independence from “the market system” — that has simply and fully become what the Marxist critic Louis Althusser called an “ideological state apparatus,” an institution that does not overtly belong to the massive nation-state but exists largely to support and when possible fulfill the nation-state’s purposes.

One of my favorite things about W. H. Auden is his tendency, when he has something very serious to say, to cast it in comic terms. In 1946 Auden wrote a poem for the Harvard chapter of Phi Beta Kappa. It is called “Under Which Lyre: A Reactionary Tract for the Times,” and you may listen to the poet read it here. As Adam Kirsch has noted, Harvard had played an important role in the war:

Twenty-six thousand Harvard alumni had served in uniform during the war, and 649 of them had perished. The University itself had been integrated into the war effort at the highest level: President James Bryant Conant had been one of those consulted when President Truman decided to drop the atomic bomb on Japan. William Langer, a professor of history, had recruited many faculty members into the newly formed Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the CIA. Now that the Cold War was under way, the partnership between the University and the federal government was destined to grow even closer.

But as Kirsch only hints, Auden was deeply suspicious of the capture of intellectual life by what, fifteen years later, President Eisenhower would call the “military-industrial complex”; and he presented his poem as a direct, if superficially light-hearted, attack on that capture. For Auden, Conant was a perfect embodiment of the “new barbarian” who was breaking down the best of Western culture from within. (See more about this here.)

Soon after his return from Harvard, Auden told his friend Alan Ansen, “When I was delivering my Phi Beta Kappa poem in Cambridge, I met Conant for about five minutes. ‘This is the real enemy,’ I thought to myself. And I’m sure he had the same impression about me.”