Once you are well inside the world of Elena Ferrante’s just-completed quartet — what English-language reviewers are calling the Neapolitan novels but what is really a single long novel published in four volumes — you are not likely to escape. The books are utterly compelling and the world they create as real as real can be. Somewhere Iris Murdoch writes of the kind of story you read to which you simply say, “It is so.” Ferrante has written that kind of story. I had been telling myself for some time that I simply no longer have the tolerance for contemporary realistic fiction. Then I started this story and thought: Oh. I just haven’t come across anything this masterful in a while.

But one thing I find curious: the universal description of these books as being centrally the story of a friendship. I think they are much better described as the story of an overwhelmingly intense, identity-forming, lifelong hatred. Much has been made of the ambiguity of the adjective in the first installment’s title: L’Amica Genial, The Genius Friend, or, in Ann Goldstein’s English translation, My Brilliant Friend — it is what each girl thinks of the other. But not enough attention, I think, has been brought to the deeply misleading, or at best ambivalent, character of the noun Amica.

There is no doubt that Elena, the narrator, is fascinated by, obsessed with, in need of, Lila; and Lila is probably just as obsessed by Elena — though Lila’s mind remains to some extent obscure to us, in part because Elena tells this story and no one can ever enter fully into the mind of another, and in part because Elena, I think, does not want us to have full access to Lila’s inner world and resists entering that world herself. When Elena gets access to documents that reveal much of Lila’s thinking, she describes their contents rather sketchily, and then destroys them, unable to remain any longer in their presence.

Elena’s destruction of Lila’s documents — though surely foreseen by Lila — is just one example of what may be the novel’s chief recurring theme: that neither woman ever misses an opportunity to harm the other, to hurt as badly as she can possibly hurt without ending their relationship forever. (To act nastily enough to cause a separation of several years, that each of them will do.) Even when they help one another, such assistance serves to acquire leverage that is later used for cruelty.

Each woman is to the other what the Ring is to Gollum: “He hated it and loved it, as he hated and loved himself. He could not get rid of it. He had no will left in the matter.” So Elena: “I loved Lila. I wanted her to last. But I wanted it to be I who made her last.” This kind of relationship cannot be described simply, but I don’t think there’s any meaningful sense in which it can be called a friendship.

The novel can and should be read as, among other things, an appropriately scalding, scarifying indictment of a society that made it impossible for Lenù and Lila to be genuine friends. They were made to be friends, I would say, deeply complementary personalities, helps and correctives for one another. But the world they are brought up in — with its harsh, rigid codes of masculinity and femininity untempered and uncorrected by a Christian message (despite the presence and apparent authority of the Church), with its relentlessly soul-grinding social and economic injustices that generate either defeatism or wild grasping attempts to escape — deforms their connection almost from the start, perverts it, twists it.

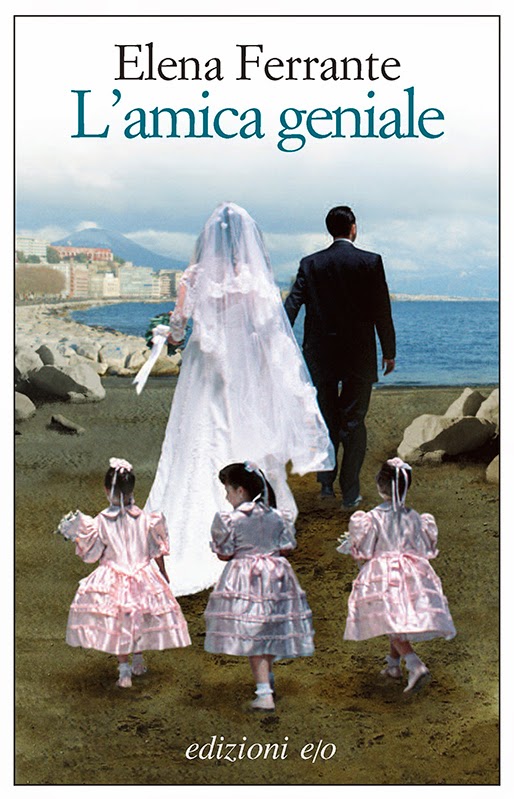

On the first disastrous day of Lila’s disastrous marriage, her brother says to her new husband, “She was born twisted and I’m sorry for you.” The new husband replies, “Twisted things get straightened out.” But the overwhelming message of the novels is that they don’t. This is not a story of a friendship. It is the tragedy of what should have been a friendship but never was.