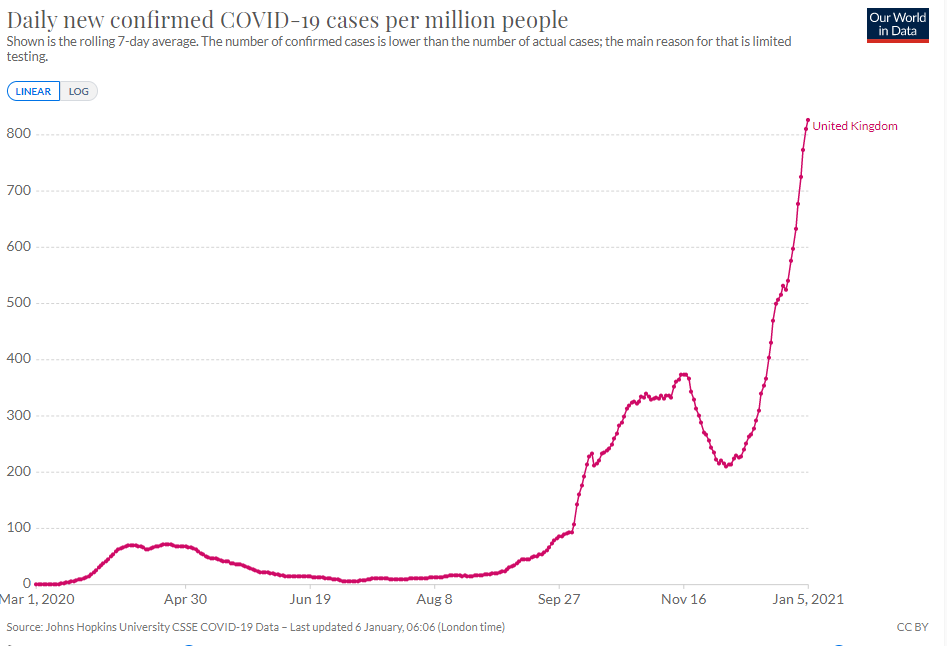

News is buzzing of a new strain of coronavirus that emerged in the United Kingdom in September, seems to be the cause of rapidly spiking case counts there, and has now reached American shores. But we have also heard alarm bells throughout the pandemic of possible dangerous new developments, most of which have not materialized. And of course, vaccination campaigns are now underway. So is this just one last scare, or is it poised to bring us back into darkness just when light was emerging?

We offer this Q&A to make sense of the new Covid strain — and what needs to be done about it.

Let’s start with the good news.

It appears that the new strain of SARS-CoV-2, which scientists call B.1.1.7 (but we will just call it “new Covid”) causes the same illness as the already known strains of the virus (which we will collectively call “old Covid”). New Covid is a respiratory illness with seemingly the same symptoms as old Covid. And from what we know so far, if you get it your odds of becoming severely ill or dying are probably not dramatically different than with old Covid. So we’re still not facing a Contagion scenario.

Now the bad news. New Covid spreads much more aggressively. That could mean the return of runaway spread like we saw in March. And it could mean that reaching herd immunity will require a larger share of people to be infected or vaccinated. So we may be looking at a deadlier and longer pandemic unless smart, aggressive action is taken right now.

The evidence comes from multiple directions.

The U.K. has good methods available to trace the spread of varying strains. For instance, it performs much more frequent genomic sequencing of viruses found in patients than the U.S. does.

Using this data, British researchers compared the infectiousness of the strains through contact tracing — studying people who had contact with those already infected with Covid. People infected with the old strain went on to infect 9.8 percent of their contacts, while people with the new strain infected 15.1 percent of their contacts. This indicates that the new strain is about 50 percent more infectious.

Another measure comes from aggregate epidemiological data of each strain’s overall rate of transmission in the population. From this data, researchers estimate that the reproduction number for the new strain — the average number of people an infected person will go on to infect — is 50 to 75 percent higher than the old strain. The new strain is quickly becoming the dominant one in the U.K.

There are good reasons to think so.

Consider the U.K., where 4 percent of the population has at some point tested positive for Covid. If the new strain evades the immunity conferred by the old strain, we would expect those people to be easily infected with the new strain. Put another way, of the people infected with new Covid, we would expect about 4 percent of them to have previously tested positive for old Covid. But if new Covid doesn’t evade immunity, we would expect to find that few people with new Covid had previously tested positive for old Covid.

The British study mentioned above helps to answer this question. Among 1,769 patients recently diagnosed with old Covid, only three had previously tested positive for old Covid. Among a different 1,769 patients diagnosed with new Covid, just two had previously tested positive for old Covid. That rate is about 40 times lower than what we would expect if the new strain evaded immunity.

This evidence is not open-and-shut, and other forms of research, such as experiments with the antibodies of vaccinated or recovered patients, still need to be done. But it is a strong signal that the immune response conferred by the old strain — essentially the same response induced by the vaccines — also protects against the new strain.

Moreover, there are several other strains of the virus that have been circulating since the early days of the pandemic that, like new Covid, have mutations in the spike protein, and the vaccine appears to work against them too.

Over the last year, the U.S. has at many points been able to stabilize Covid outbreaks, stopping runaway spread and seeing modestly declining case curves, though without ever eliminating the virus. In other words, at best we’ve been able — barely — to tread water. But it wouldn’t take much added weight to sink us.

The new strain may be too much added weight. For a measure of the effectiveness of our response so far, consider the virus’s reproduction number — the average number of people an infected person will pass the virus along to. When this number is below 1, new infections will decline each day. When it’s above 1, they will grow exponentially.

In the U.S., this number seems to have been bouncing between 0.8 and 1.3 since April. If the new strain is indeed 50 percent more infectious, then with the measures we’ve been employing we may see a reproduction number between 1.2 and 1.9.

That would be bad. Instead of peaks and troughs of outbreaks across different regions of the country, we would see an ever-rising tide. It’s possible that the country could return to something resembling the runaway situation New York faced in March, but now everywhere and all the time until we reach herd immunity.

And about that: Herd immunity may become harder to reach, as more people need to be infected or vaccinated to stop a virus that spreads more aggressively. In other words, between the new strain and the slow vaccine rollout, a great many more people might become sick and die before we reach herd immunity than if we were only dealing with old Covid.

It gets worse. There is still uncertainty about the lethality of the new strain. While it could be the same as or lower than old Covid, it could also be around 20 percent higher, a hefty added toll when death counts are already so high. More infections also means more chances for the virus to mutate further, which could lead to it becoming more deadly, even more infectious, or more able to evade immunity.

It’s possible.

There have been warnings earlier in the pandemic of worrisome new strains that haven’t materialized as real problems. So let’s imagine it’s a month or two from now and the new Covid threat has fizzled. What happened?

Sometimes particular viral strains become increasingly prevalent because of chance rather than any actual advantages at transmission. Whatever strain of a virus happens to arrive in a region that is unprepared to contain it can quickly grow in prevalence simply because it was in the right place at the right time, not because it is intrinsically more contagious. This “founder effect” may be what accounted for the dominance of one strain of the virus that for a time worried scientists earlier in the pandemic.

But the new strain in the U.K., which is spreading quickly under lockdown conditions in areas where old Covid is already circulating widely, probably cannot be explained by such effects. It appears to be spreading quickly both in southeastern England, where it was first detected, and also in regions across the United Kingdom, suggesting that it has the ability to spread faster than old Covid wherever it is introduced. New Covid is still mostly confined to the U.K., but it also now accounts for a quarter of cases in Ireland. In Denmark, it has gone from 0.2 percent to 2.3 percent of cases in just three weeks.

But these findings are still preliminary, and it is always possible that new Covid will not spread as quickly in other countries under different conditions. Or perhaps its advantages will diminish as weather improves in the spring; coronaviruses may be less transmissible in warmer weather, and that may be especially true of new Covid. Other mutations may also emerge that could make the virus substantially less lethal: A variant that became prevalent in Singapore before the country eradicated the virus was much less severe than other Covid strains, and one of new Covid’s mutations is similar to the mutation in the Singapore strain. While there is no evidence so far that new Covid shares the Singapore strain’s mild severity, the presence of similar mutations might allow it to evolve in a less severe direction in the future.

Since we can’t see the future, perhaps these questions are better: If the new Covid threat fizzles, what damage will have been done by responding aggressively to what turned out to be a false alarm? And how would that damage compare to a world where we fail to respond to the alarm but it turns out to be true?

Perhaps the biggest concern about how we might respond to the new strain is that some countries, including the U.K., are already proceeding with delaying the second vaccine dose, which could lead the virus to develop resistance against the vaccine — a nightmare scenario. This measure remains a deeply risky gamble. We also of course don’t want more lockdowns and disruptions that turn out to be unnecessary.

But most of the measures that could be taken to respond more effectively to new Covid are things we should be doing anyway against old Covid. Which brings us to…

The measures that have worked against the old strain should still work against the new strain. The problem is that when facing an even stronger foe, we will need all the weapons we used before — but these may no longer be enough.

There is much else that could still be done.

To start, the United States should be doing much more sequencing of Covid genomes to be able to detect and track new mutations in the virus. The Washington Post reports that we currently sequence the genome for only 0.3 percent of cases, ranking us 43rd in the world — far behind the U.K.’s 7.4 percent.

It is an open question whether PCR tests in the U.S. might be adapted to distinguish cases of new Covid from old, as has already been done in the U.K. It’s unlikely that we can totally stamp out new Covid through identifying and isolating cases at this point. But small differences matter: The more chains of infection we can cut off, the longer we can delay growth, the closer we get to mass vaccination, and the fewer lives a new runaway phase would claim.

Public health experts are also already debating delaying the second dose of vaccines to allow more people to receive the first dose, which on its own confers significant immunity. (This too is already happening in the U.K.) But some scientists worry that just one dose will create a weaker immune response, to which the virus could more easily develop resistance. It is a genuinely difficult question: If delaying the second dose means more people receive the first dose, this could buy critical time to slow the new strain while more vaccines are produced. But a new strain that is resistant to vaccines would be disastrous.

Other measures should be on the table too, such as travel restrictions from regions where the new strain is rapidly spreading. And any regulatory or funding barriers to rapid research on the new strain that can be removed should be.

But there is a basic limitation to these suggestions: The steps that most need to be taken in response to the new strain are the same ones that should have been taken for the last year anyway, but that our government has proved largely unable or unwilling to take. An effective regime of testing, tracing, and isolating, for example, has been needed throughout the pandemic, but never really implemented.

Meanwhile, in the U.S. vaccination rollout, overly complex eligibility and prioritization structures, potential punishments for hospitals that violate prioritization guidelines in order not to waste doses, inter-governmental squabbling, other red tape, and simple lack of willpower have left millions of doses languishing in freezers across the land instead of injected into arms. What under the old strain would have been a frustrating delay and missed opportunity, under the new strain could constitute a looming disaster.

For the first time in the pandemic, our country has a silver bullet. Our leaders must find the discipline to deploy it now.

During Covid, The New Atlantis has offered an independent alternative. In this unsettled moment, we need your help to continue.