The Case Against “STEM”

Notice: Undefined index: gated in /opt/bitnami/apps/wordpress/htdocs/wp-content/themes/thenewatlantis/template-parts/cards/25wide.php on line 27

How blurring the line between science and technology puts both at risk

Science and technology support innovation, economic growth, and military might, making them central pillars of geopolitical competition. For the last three decades, the United States has been mostly unchallenged in its role as the world’s leader in scientific and technological research. But in recent years the country has come to face an explicit challenger in China.

As the United States seeks to shore up weaknesses and ensure leadership for this century, we must recognize the key role that global talent plays in driving progress on the frontier, our country’s long history of recruiting this talent, and how to fully leverage this advantage with a more proactive approach.

Why some countries stay at the cutting edge of science and emerging technologies is a complex question, the topic of countless books and historical studies. But one crucial factor is the sheer number of smart, talented people they have.

Like any other industry, research requires physical capital and infrastructure: powerful computers to store and analyze data, state-of-the-art research labs with expensive equipment, a capable manufacturing industrial base. But to some extent these are all second-order consequences of technological and scientific advancement. Creating the next generation of microprocessors, making breakthroughs in computer-vision algorithms, building the most efficient solar panel, or developing the highest-performance rocket launch system requires the most brilliant minds in those fields working together, usually in a closely connected intellectual community.

Put differently, superstar talent is the most precious resource in the process of producing innovation. The cost of capital is at an all-time low for governments, so plowing billions into the development of physical infrastructure is not in principle prohibitive. But the world’s geniuses are inherently scarce, and so their choice of where to live and work is critical. The advantage to a country that attracts geniuses compounds over time, as clusters form around them — talent attracts more talent — which helps all the individuals and firms in such clusters become more productive than they would be in isolation.

Historically, competition over top talent has been a major component of conflict between great powers, and has been especially important for the United States. In many ways, the twentieth century is a story of how America rose to technological and scientific heights by recruiting and integrating the top minds of its rivals. In 1900, the United States was considered a bit of an intellectual backwater, with the strongest scientific work happening in Europe. German research universities in particular were the envy of intellectuals in America and around the world. But between 1930 and 1960, the United States received a massive injection of scientific talent from Germany and Austria, arguably the largest intellectual transfer of the modern era.

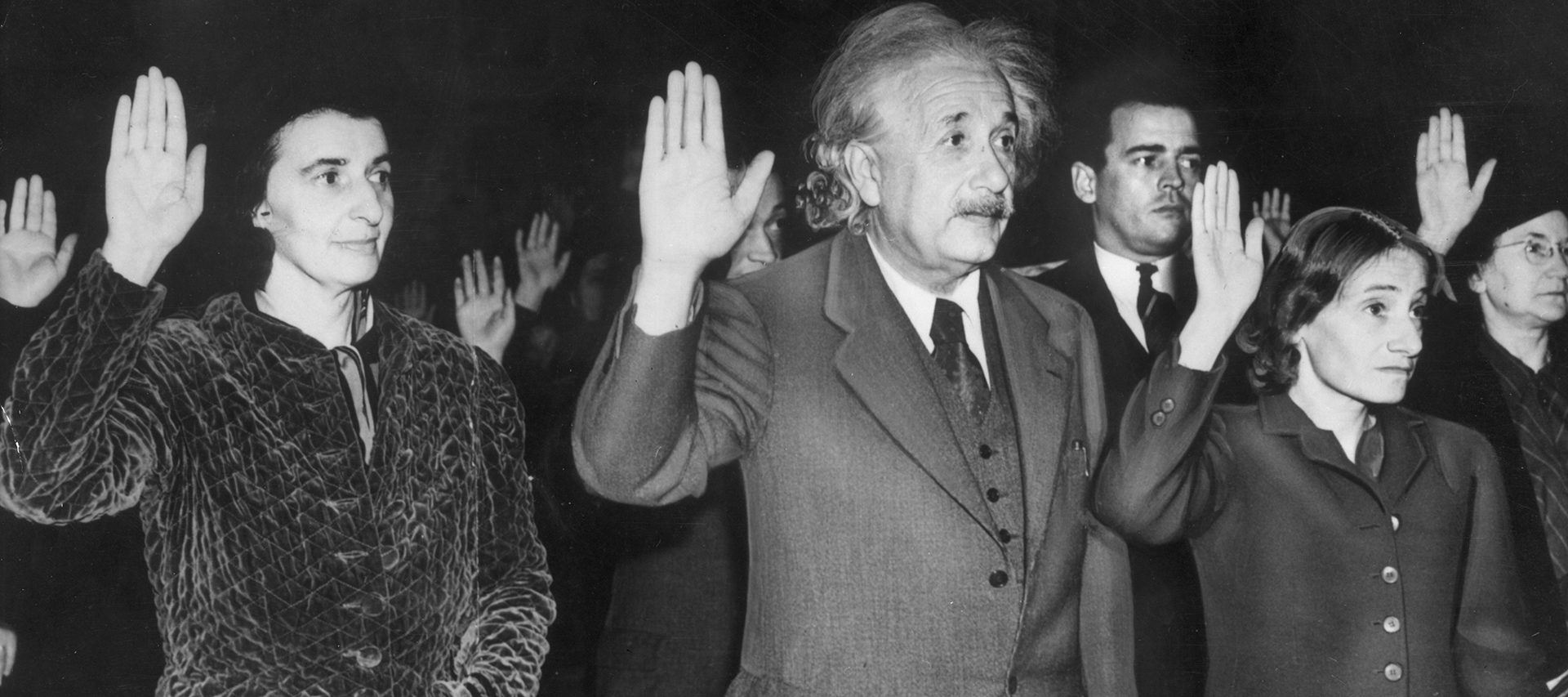

This talent transfer happened in a few waves. The first came in the 1930s with the Nazi persecution of Jews and political dissidents, who were dismissed from university posts and fled. According to the German economist Fabian Waldinger, this group included 15 percent of German physicists, whose publications accounted for 64 percent of German physics citations. The Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University took it upon itself to actively recruit these academics and help them find positions in the United States. Some of them — intellectual superstars like Edward Teller, John von Neumann, Leo Szilard, and Albert Einstein — made the Manhattan Project possible. Describing the importance of these scientists to the Allied war effort, Churchill’s military secretary Sir Ian Jacob is said to have remarked that the Allies won “because our German scientists were better than their German scientists.”

The migration of these luminaries to the United States also improved the productivity of the native-born American scientific community. A 2014 paper on the impact of this wave of talent examined chemical patents as a case study and found that the influx of German émigrés led to a 31 percent increase in patents filed by American inventors.

The second, and far more controversial, wave of talent immigration to the United States occurred after the Second World War, during the early stages of the Cold War. Both the United States and the Soviet Union raced to recruit — or in some cases, forcibly kidnap — top German scientists, technicians, and engineers. Under Operation Paperclip, American intelligence agents brought to the United States about 1,600 scientists, along with their families, while the Soviets’ Operation Osoaviakhim brought somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 to the Soviet Union. While the Americans brought fewer experts altogether, they may have snagged the brightest stars. Included in the group was the German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, who became the chief architect of the Apollo program’s Saturn V rocket, and Adolf Busemann, who pioneered the concept of swept wings in aeronautics that significantly improved aircraft performance at high speeds.

The economic value of the scientists brought to America under Operation Paperclip is difficult to quantify, as many of the innovations were military in nature but also had other applications. Spillover effects, whereby the scientists challenged and inspired their domestic counterparts to work harder or discover new ideas, are likewise difficult to account for but likely contributed a great deal to American science in the postwar period.

Some of these scientists were recruited, others kidnapped; some were conscientious objectors to the Nazi regime, others willing adherents. The ethics of the program remain a topic of heated debate. But the reason the scientists were (mostly) welcomed into the United States at the time is that their contributions were thought to be crucial for American victory in the Cold War. Better that their studies continue in the United States than in the Soviet Union, the thinking went.

Thus the Manhattan and the Apollo projects — arguably the two most impressive scientific accomplishments of the twentieth century, and certainly the two that solidified America’s technological leadership — were achieved through a combination of international scientific talent and American scientific institutions.

A third wave of international talent recruitment could perhaps be identified in the waning years of the Cold War, as Soviet mathematicians and other academics began to look for an escape hatch. American universities suddenly had their pick of top Soviet scientists and were bidding against each other for the brightest stars. A 1990 New York Times article quoted one American mathematician saying that these Soviet academics were “replenishing the mathematical juices of the United States,” while one Soviet émigré reported hearing “almost every day” from other Soviet scholars who wanted to visit or live in the United States. There was even a policy proposal at the time to subsidize employers of these scientists, in the hope that we could assimilate all this newly available global talent as rapidly as possible.

The net effect of these three waves has been America’s consistent domination of international science and technology. Using the Nobel Prize in Physics as a rough proxy, American scientists were involved in only three of the thirty prizes awarded between 1901 to 1933. From 1934 to 2020, Americans have been involved in roughly two thirds. And an enormous share of American Nobel laureates have been either first- or second-generation immigrants from these three waves.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the United States has effectively been able to rest on its laurels. No country has seriously attempted to challenge the U.S. in its leadership status. We ceased needing to actively recruit immigrant inventors because they naturally wanted to come to the global center for talented scientists and engineers. William Kerr, in his book The Gift of Global Talent, documents that between 2000 and 2010, more immigrant inventors came to the United States than to the rest of the world combined. We built it, and they came.

But in recent years, this has begun to shift. China has explicitly taken up the challenger mantle that the Soviets dropped. China has ambitious plans to take industrial leadership in artificial intelligence, quantum computing, semiconductor manufacturing, and other high-tech fields by 2030. Whether or not they hit the specific target date, they are making progress and challenging American leadership in a way we haven’t seen in thirty years.

Central to China’s strategy has been its attempt to reclaim human capital from the United States, primarily in the form of the Thousand Talents Plan. This program aims at recruiting the talented Chinese graduate students and university professors currently enrolled or teaching at foreign universities (particularly in the United States) and getting them to start businesses or contribute to scientific advancement back home. The program also aims to do the same for international talents that are not originally from China.

According to a 2020 Brookings Institution report, “Chinese officials see the United States’ continued ability to attract and retain Chinese talent as a serious impediment to their technological ambitions,” while President Xi Jinping has often described talent as “the first resource” in China’s efforts to achieve “independent innovation.” In 2016, the Chinese Communist Party created its “Outline of the National Innovation-Driven Development Strategy,” writing that “the essence of being innovation-driven is being talent-driven.”

And it’s not only China — countries from all over the globe are becoming more ambitious about poaching top international talent. Canada has for years been putting up billboards in Silicon Valley advertising its comparatively lax immigration system. And the United Kingdom recently launched an ambitious new visa category aimed at attracting an unlimited number of talented scientists and entrepreneurs.

Meanwhile, the United States has been consistently putting up higher barriers for skilled migrants. The Covid-19 pandemic might serve as a breaking point of sorts, as talented international students, in particular, are forced to take a pause and reconsider their best career options.

American leadership in science and technology is vital for ensuring that the United States continues to maintain its position as an economic and military superpower, and particularly that it does not lose it to China. Research leadership is also a way to ensure that the future of scientific and technological development happens in a liberal democracy that respects human dignity, rather than a brutal dictatorship that doesn’t.

Part of what is at stake is choices about which technologies become globally adopted. Today’s technologies may seem as though they were an inevitable result of technical progress, but they were not. Historical contingencies — including cultural norms, political priorities, and policies — could have led us down different paths. For instance, the way the United States turned away from mass transit infrastructure toward highways in the mid-twentieth century shaped the development of cities, family life, employment, and transportation broadly in our country differently than in Europe.

In addition to the ways we can choose between technologies, we can also shape how particular technologies are developed. Georgetown researcher Tim Hwang, in the recent report “Shaping the Terrain of AI Competition,” writes that China is generally considered to have an advantage over the United States in AI research, because China has a larger population and near-nonexistent privacy concerns about gathering data on people. But, Hwang argues, this advantage can be offset by strategic public investment into and promotion of AI techniques that either reduce the amount of data required to develop cutting-edge AI systems or boost the prospects of simulation learning such that large data centers replace or lessen the need for the kinds of real-world data collection that pose privacy concerns.

The decision between these two approaches will be made in the near future — or is already being made as large AI companies choose where to invest. But we can influence the decision only if we are on the frontier ourselves. That is, we can shape moral choices about how technologies are being developed only if we offer an environment to which top researchers will be attracted.

Consider gene editing as another example. The American public, policymakers, and watchdogs have essentially no control over or input on developments in China. Consider the CRISPR-baby scandal in 2019, when a Chinese researcher manipulated the genomes of twin girls, with no direct benefit to them, while in the process breaking safety and ethics norms. We have a difficult time even knowing what is happening in Chinese research labs, much less regulating it. We should thus make it more difficult for unethical advances to be made in countries like China by offering a more competitive research environment ourselves. If the United States makes a concerted effort to attract and retain top scientists from around the world, our moral standards for science and technology will better be able to shape the direction of global research.

Both the national and the global interest cannot allow these kinds of technical and ethical decisions to be left to China. The country not only operates a sophisticated surveillance regime on its own people but aims to export it around the world. The Chinese Communist Party aims to show developing countries that a fundamentally illiberal model of governance is not only possible but desirable. Chinese techno-hegemony is central to this claim, and so must be resisted with renewed American leadership.

There may be reasons to be skeptical that China will be able to overtake the United States in technological and scientific leadership. China has not been able to assimilate immigrants at anywhere close to the level that we have. China is betting that its larger population, more streamlined and top-down state apparatus, and more generous research support will be able to out-innovate the more bottom-up American system. But drastically falling birthrates and an excessive reliance on easily quantifiable metrics may prevent them from making much progress on the frontier after they have caught up. Consider, for example, China’s plan to publish fifty world-class AI textbooks. This may be a useful political soundbite, but as a strategy it makes little sense, as no more than the first few would likely be helpful.

China pessimists essentially see the country as a much larger Japan: There was similar alarm in the 1980s and 1990s that that country would overtake us in technological development and economic growth — until their low birth rates caught up with them.

But so what if the dangers of Chinese technological hegemony do turn out to be overstated? If we double down on our open innovation system, solidify American leadership for the next few decades, and then it turns out that China stagnates anyway, is that a great loss? America will be the better for it, regardless of whether China ends up posing the long-term threat we fear.

America should not let our advantage in attracting global talent slip away. While our momentum is fading, we still have the most researchers working on the cutting edge of various fields, and that provides a certain kind of inertia. But what would it look like for the United States to take this historical advantage in global talent acquisition seriously? We need not go to the extremes of Operation Paperclip to do much more than we are doing now.

First, there is the obvious need for immigration reform. We have tens of thousands of smart people who would like to live and work here but are stymied by our current immigration system. There have been many proposals to make it easier for highly skilled, ambitious, technically-minded immigrants to live and work in the United States. Some have suggested we should staple green cards to the diplomas of foreign students studying here. Others have argued that we should move to a points-based immigration system like Canada or Australia that better prioritizes highly skilled workers. One proposal for a “Heartland Visa” aims to allow cities and metro areas to have more say in determining immigration flows to their regions based on the types of workers that best fit their industries. Others have suggested the creation of a startup visa to encourage foreign-born entrepreneurs to create new businesses here. These proposals all have merits, and we should consider implementing some combination of them.

But we should go beyond these reactive measures and take a more proactive approach to talent immigration. Today we grudgingly let the most talented individuals apply to live here; we do not actively recruit them. We should, as even if we do make our immigration system less restrictive, this will not ensure that the world’s most talented scientists come here. We face competition for talent from adversaries like China, but also from other rich, immigrant-friendly countries like Canada. And as the economies of developing countries continue to grow, there will be more opportunities for scientists in their home countries and less reason for them to uproot their lives to work in America.

Top corporations have elaborate talent selection departments or contract with headhunting agencies precisely so they can identify talented individuals and bring them to the company. Often, this means recruiting talented workers from abroad and hiring them using programs like the H1-B or L-1 visas. But leaving the top pickings only to multinational firms reflects a bias against startups and distorts the labor market for these talented workers. Instead, the United States government should take some responsibility for recruiting talent for the country.

The current American immigration apparatus is not set up to identify and recruit the smartest, most promising candidates from around the world. Rather than considering the full array of potential benefits from recruiting immigrants, concerns about identifying and stopping threats dominate the day-to-day work of America’s immigration agencies — which currently sit within the Department of Homeland Security. The main job of immigration agents seems to be “avoid letting in terrorists” rather than “maximize the growth potential of the United States.”

To correct for this deficiency in our existing immigration system, imagine creating a new department within U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services or the State Department whose sole goal was to identify talented scientists, engineers, academics, and supply chain managers from abroad, then proactively recruit them to the United States with an offer of permanent residency or even citizenship. Call it a Department of Promigration, to borrow a term coined by economic historian Anton Howes.

To provide an incentive to recruit top talent, promigration agents — acting as talent scouts — could be given bonuses based on the performance of the individuals they let in, with benchmarks around high salary, company formation, academic awards earned, high-quality patents filed, paper citations, grants won, or any number of metrics of success we care about. Rather than selecting agents with national security backgrounds, the Department of Promigration should focus on hiring agents with technical and scientific backgrounds who will be better able to identify scientific talent when they see it.

Another approach to promigration would be similar to the United Kingdom’s new Global Talent visa. The British government has designated private entities like Tech Nation that can sponsor a number of visas for talented workers and entrepreneurs. These organizations find promising young people from around the world, sponsor their visas, and then help them get established in the country. This provides an opportunity for civil society organizations to help vet, identify, and support promising candidates. The Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton played this role for the United States in the lead-up to the Second World War, and similar groups could do so again. We could identify or create a handful of non-governmental institutions affiliated with academia and industry and allocate them a number of visas for sponsoring promising talent from around the world.

The United States stands at a crossroads. Historically, our greatest advantage has been our ability to integrate the greatest minds from around the world into our society, where they find not only the resources to do their work but also the institutional constraints to channel that work in productive directions that align with the aims of the country.

As we face renewed competition for technological and scientific leadership, this time from China, we should return to our roots as a proactive recruiter of global talent and lay the groundwork for the next generation of immigrants who can win the 2035 Nobel Prize in Physics for the United States.

During Covid, The New Atlantis has offered an independent alternative. In this unsettled moment, we need your help to continue.