It was more than seven years ago that President Bush met with his Russian counterpart, then-President Vladimir Putin, and uttered the now-infamous words: “I looked the man in the eye. I found him to be very straightforward and trustworthy…. I was able to get a sense of his soul.” Looking back, the president must surely regret this statement. The ensuing years have shown that, under Putin’s stewardship, Russia is rapidly reverting to its old authoritarian ways (minus the communist ideology): power has been centralized, energy and media companies have been nationalized, Kremlin critics have been assassinated, and opposition party members have been arrested and excluded from what many consider rigged elections. (In October 2007, riffing on President Bush’s unfortunate remark, Senator John McCain quipped, “When I looked into Putin’s eyes, I saw three letters: a K, a G, and a B.”) Worse still, there is no sign that Putin is willing to relinquish control anytime soon. This past spring, he completed a carefully choreographed transition from president to prime minister, essentially handing over the presidency to his trusted understudy Dmitry Medvedev while, by all accounts, still holding tightly onto the reins of power from his new perch.

And Putin has done more than alter Russia’s domestic politics. Today, it increasingly looks like Moscow is also revisiting its Cold War-era bullying habits on the international stage, making use of its plentiful energy resources to exert political influence over its former Soviet satellite states. The most notable example of this so-called “pipeline diplomacy” occurred in January 2006: ensnarled in a pricing dispute with Ukraine, Russia’s natural gas company and sole gas exporter, Gazprom (of which then-Deputy Prime Minister Medvedev was chairman), stopped sending gas to Ukraine to starve the country of needed energy and hasten a favorable conclusion. Ukraine responded by siphoning off Russian gas destined for consumers situated further west, leaving several downstream European countries with an average of 30 percent less Russian gas for three days in the dead of winter. Russia has had similar pricing disputes with Moldova, Georgia, and Belarus.

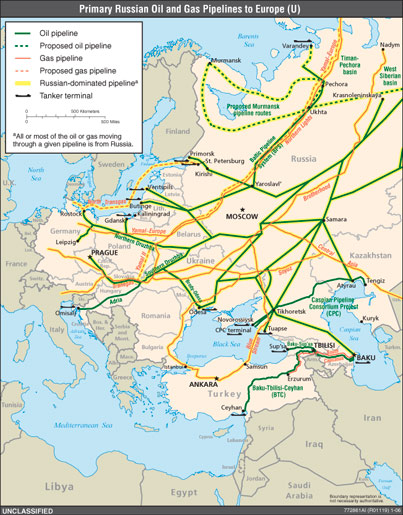

|

| SOURCE: U.S. Department of Energy. (To see a larger PDF, click here.) |

Gazprom has also raised some eyebrows by its involvement in two new major pipelines — the Nord Stream and the South Stream. When finished — a prospect several years away — these two Russia-Europe gas pipelines will circumvent several countries, like Ukraine and Belarus, that now have pipelines going through them. In light of Russia’s recent dispute with these transit countries, many observers think these new pipelines will allow Russia to act like a boa constrictor, surrounding these states, ready to squeeze them when it seems expedient. (Gazprom has not indicated, however, that it plans to cease using current lines, and in fact is looking to enhance the capacity of the Yamal-Europe pipeline that runs from Russia to Western European markets through Belarus and Poland.) The two new pipelines are also expected to solidify Western Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, putting it in the same vulnerable position in which much of Eastern Europe now finds itself. The South Stream pipeline has the added value of presenting a direct challenge to the U.S.- and E.U.-backed Nabucco pipeline, a proposed Russia-free route from the Caspian Sea to Europe.

Several European political leaders have begun to fret about whether Russia is a reliable energy partner. Their anxiety is justified. Natural gas currently makes up about one quarter of Europe’s energy consumption, and Russia — endowed with the greatest known gas reserves in the world — supplies 29 percent. In the coming years, according to a European Commission report, Europe’s demand for gas will grow substantially faster than its domestic production, meaning that its dependence on Russian gas will likely increase. Some in Europe and beyond are concerned that Russia will exploit this energy relationship to manipulate gas prices (unlike oil, there is no global price for gas since gas is difficult to transport) and to strengthen its hand in political disagreements, like the accession of Eastern European countries to NATO, Kosovo independence, and a U.S.-sponsored missile defense program on its borders. Conventional wisdom suggests that Russia has Europe bent over the proverbial barrel.

But this is certainly not the whole picture. Russia is heavily dependent on revenues generated from its energy sector to keep its economy afloat. Gazprom alone is responsible for some 25 percent of Russia’s tax revenues and, as reported by the U.S. government’s Energy Information Administration, the energy sector provides 20 percent of Russia’s gross domestic product. Europe has historically played a disproportionate role in expanding Gazprom’s — and by extension Russia’s — booty. According to Gazprom’s own data, at the beginning of the decade, Europe consumed about one-third of Gazprom’s production, yet was responsible for 60 percent of the firm’s total revenues. This imbalance was the result of greatly subsidized gas prices to former Soviet states and Russia’s domestic market.

These petroleum-generated revenues are necessary for Moscow to address several perennial domestic issues. Despite a rapidly expanding economy over the last few years — 8.1 percent growth in 2007 — the Russian economy’s growth rate is currently being outstripped by its inflation rate by nearly 4 percent. Moreover, Russia is susceptible to “Dutch disease,” an economic condition whereby natural resource sales cause a country’s currency to appreciate, making the rest of the country’s industries less competitive on the global market. This is to say nothing of the deluge of social challenges Russia faces going forward: a shrinking population, disintegrating social programs, rampant alcoholism, and an emerging HIV/AIDS epidemic. Russia’s energy sector is a crutch on which the rest of the country leans. While Russia is using its energy policy to raise its profile on the global stage, it may be more interested for the time being in using the revenues generated from this policy to prop up its flagging domestic economy. Essentially, Russia is a real life Wizard of Oz — a superficially powerful giant, but behind the curtain frail and weak. It needs to keep its taps open and the gas flowing not only to regain its global status as a superpower, but to survive.

The real question for Europe regarding Russia’s reliability as an energy supplier may not be will, but can Russia deliver its petroleum resources to the market?

Despite record-high revenues, Russia’s energy sector is flawed: easy-access petroleum fields in western Siberia are drying up, other fields in eastern Siberia and elsewhere are expensive to develop, and gas pipelines are operating at capacity and in desperate need of repair. Moreover, many observers fear that Russian energy companies, for all their wealth, lack the funds and expertise to address these problems on their own.

To compound the problem, Russia’s domestic demand is also expected to increase over the coming years, leaving less gas available for export. In January 2006, in the midst of a particularly cold winter, Russia required more of its own gas to meet domestic demand and was unable to meet commitments to European consumers.

Steve LeVine, a longtime observer of Russian and Caspian energy issues and author of the excellent 2007 book The Oil and the Glory, believes that concerns about Russia’s future production and transportation capacity are likely overstated. Russia and energy-rich Caucasus and Central Asian states have had on-again-off-again relations with Western energy companies, turning to them in times of need and booting them in times of prosperity. As Russia approaches the point of being unable to meet domestic and foreign demand, it will likely become more amenable to foreign assistance. Foreign companies looking for revenues will certainly return to Russia without much thought about having been spurned in the past. That said, energy sector infrastructure takes a long time to develop and is an expensive endeavor, and Europe may find itself in the future dealing with a Russia that simply cannot meet its commitments.

For the time being, Russia does have a stopgap measure to keep the gas flowing: land-locked Central Asia. Russia is currently using gas from the central Asian states to supplement its diminishing domestic supplies. In May 2007, it struck a deal with Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to improve old and build new pipelines to Russia.

With all this in mind, it is worth revisiting the Russia-Ukraine gas dispute. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia’s pipelines have acted like a “steel umbilical cord” — they have kept the infant Caucasus and Central Asian countries producing energy and Eastern European countries transporting energy as de facto parts of the motherland. As part of this arrangement, Eastern Europe received discounted gas in a barter agreement that allowed Russian and Central Asian energy resources to flow through to the west.

At the time of the Russia-Ukraine dispute, the relationship between the two was seriously strained. Ukraine was slouching westward, having recently gone through the Orange Revolution and the rise of pro-Western President Viktor Yushchenko. As such, it is difficult not to see Russia’s hardball tactics through a political lens and as a natural extension of the previous relationship, with Russia acting like a possessive mother punishing a child who dares to act against her will.

Around the same time as the Ukraine dispute, Russia was “renegotiating” energy contracts with Moldova, Georgia, and Belarus. The case of Belarus is interesting, because the country has remained closely aligned with Russia since the fall of the Soviet Union. But this allegiance did not save it from experiencing Russia’s stern bargaining techniques — Transneft, Russia’s state-owned pipeline company, ceased sending oil to Belarus for three days in January 2007.

Following the Belarus dispute, Medvedev, then deputy chairman of Gazprom, stated that Russia’s gas company was merely “shifting all our relations with customers to a market basis.” While rhetoric from a Russian official should rarely be taken at face value, Medvedev may have been speaking truthfully in this instance. Since bringing Eastern Europe gas prices closer to market rates in 2007, Russia saw its revenues from these countries increase by 93.5 percent per year. By 2011, these countries are scheduled to pay the same prices for Russian gas as does Western Europe. Today, Russia appears to prefer the benefits of energy revenues to those of regional dominance.

Perhaps the greatest evidence to support Medvedev’s assertion is the fact that the Kremlin has taken steps to allow for the increase in prices at home. According to Gazprom’s 2006 annual report, Gazprom has permission to raise domestic prices for the regulated sector significantly — up to 15 percent in 2007, 25 percent in 2008, 20 percent in 2009, and 28 percent in 2010. By 2011, domestic prices could conceivably be equal to European prices, minus transportation costs and custom duties.

Russia’s decision to wean Eastern Europe and domestic markets off gas price subsidies has a potential additional benefit: higher prices should reduce demand in these markets for gas, thereby freeing up more for exports. This could help Gazprom meet its commitments to foreign consumers and increase its — and the Kremlin’s — revenues.

This is not to say that Europe should be sanguine. Russia most certainly has aspirations to be a prominent actor outside its borders, and will likely continue attempting to influence regional and global developments, often taking positions contrary to the West’s desires.

It should also be stressed that Russia’s capacity to diversify its pipelines to Europe puts Russia in a position to divide and conquer the continent in the future. Acting like a heart, Russia pumps gas and oil through an expanding number of arteries. The more alternatives it has, the more it can shut down one line without significantly affecting other countries or its petroleum revenues. Considering the direction in which Putin has steered Russia, a stronger Russia with an energy weapon in its arsenal is not a comforting thought.

Still, one should be careful not to confuse the Kremlin’s harsh tactics with its overall strategy. Right now, Russia, while relying on its old ways of doing business, is likely consumed with worries about its economic growth and social stability. As such, it is dependent on keeping its gas flowing and getting market value for the goods to pay for its much-needed domestic reforms.

Ironically, Russia’s aggressive gas diplomacy may ultimately put it in a weaker position, as it will encourage Europe to consider alternative sources for energy. If Europe can unify its energy policy and diversify its supply sources — two immensely challenging tasks — Russia may find itself without the energy arrow in its diplomatic quiver.