The Population Control Holocaust

Notice: Undefined index: gated in /opt/bitnami/apps/wordpress/htdocs/wp-content/themes/thenewatlantis/template-parts/cards/25wide.php on line 27

Philanthropy has many wonderful qualities — and never tires of proclaiming them, for one quality it sorely lacks is humility. It regularly thumps itself on the back, for instance, for devoting some $300 billion a year to good causes. And though philanthropic spending on social causes is dwarfed by that of the government, foundations proudly claim that dollar for dollar their spending is in fact more effective than the government’s. While government tends to stick with the safe and the routine, philanthropy regularly and energetically seeks out the next new thing; it claims it is at the cutting edge of social change, being innovative, scientific, and progressive. Philanthropy, as legendary Ford Foundation program officer Paul Ylvisaker once claimed, is society’s “passing gear.”

Indeed, philanthropy increasingly prides itself on its ability to shape and guide government spending, testing out potential solutions for social problems and then aggressively advocating for their replication by government. Any employee of a philanthropic organization can immediately tick off a list of major accomplishments of American foundations, all of which followed this pattern of bold experimentation leading to government adoption. For example, Andrew Carnegie’s library program pledged funding to construct the buildings, if the local municipalities would provide the sites and help pay for the libraries’ operation. The Rockefeller Foundation funded a moderately successful hookworm abatement program in the southern United States, which strongly involved local governments. The Ford Foundation’s “gray areas” project in the 1960s experimented with new approaches to urban poverty that then became the basis for the Great Society’s War on Poverty.

And yet, in all this deafening clamor of self-approbation, we rarely hear from these foundations about another undertaking that bears all the strategic hallmarks of American philanthropy’s much-touted successes, with far more significant results: that the first American foundations were deeply immersed in eugenics — the effort to promote the reproduction of the “fit” and to suppress the reproduction of the “unfit.”

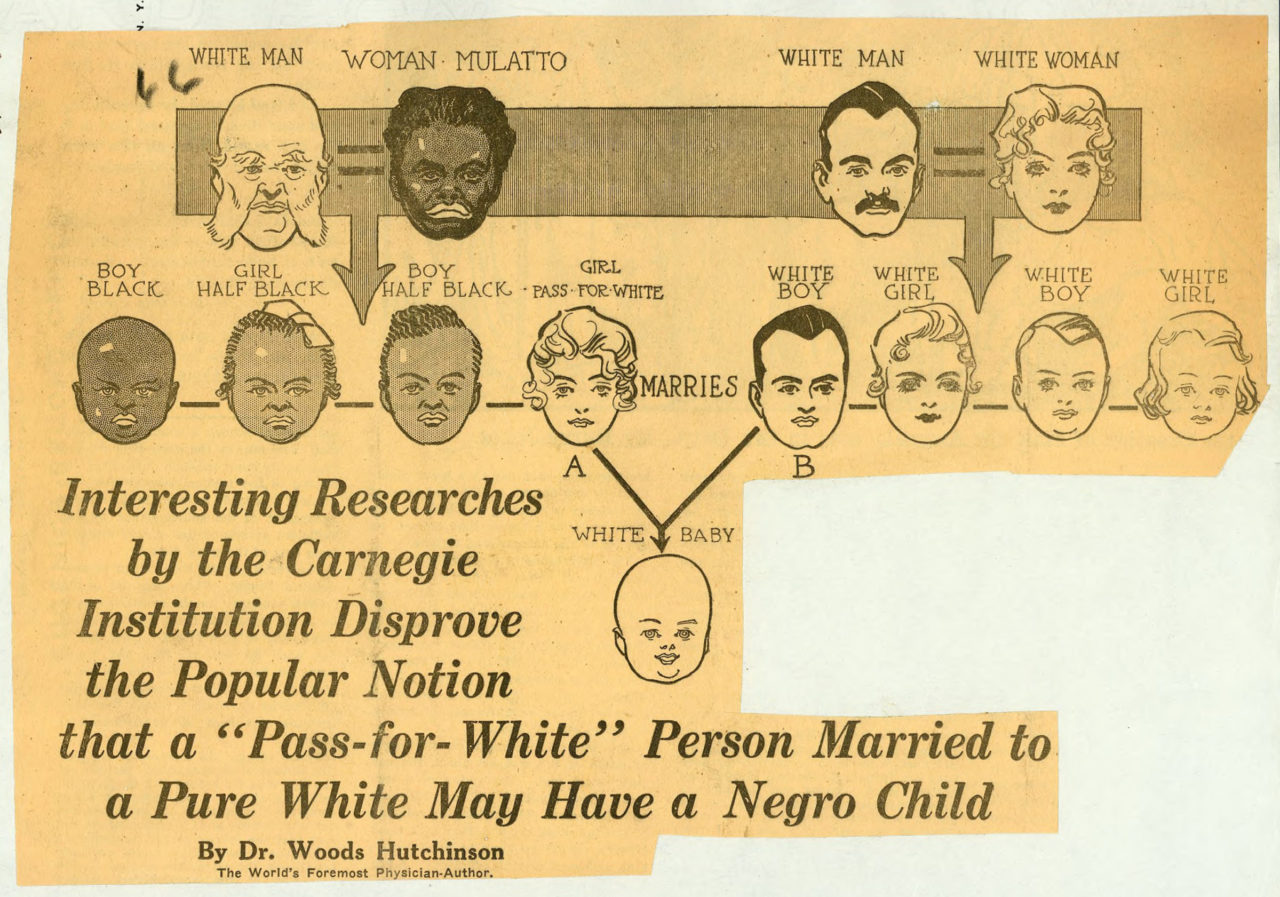

Although some of its animating ideas of course reach much further back into history, modern eugenics began with the mid-nineteenth-century work of Sir Francis Galton, the great English statistician and cousin of Charles Darwin. Galton proposed that talent and high social rank had hereditary origins, and that society could and should give monetary incentives for marriages of and progeny from eminent couples. By the turn of the twentieth century, eugenics was considered a cutting-edge scientific discipline backed up by a growing political and social movement — and therefore a particularly worthy candidate for philanthropists’ attention. It is no surprise, then, that the first major foundations devoted resources not only to the research behind the movement, but also to lobbying for government adoption of eugenic policies: at the federal level, restricting immigration of the “unfit”; at the state level, their mandatory institutionalization and sterilization.

Eugenics was American philanthropy’s first great global success. It inspired and cultivated programs around the world, but nowhere with more consequence than in the nation that sought most fervently to imitate America’s eugenic example, Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich.

How did American philanthropy become involved with so reactionary and misanthropic a venture as eugenics? As recent scholarship on eugenics has shown, the movement was not considered reactionary at the time. To the contrary, eugenics was very much an essential feature of the American progressive movement at the beginning of the twentieth century.

America’s first general-purpose philanthropic foundations — Russell Sage (founded 1907), Carnegie (1911), and Rockefeller (1913) — backed eugenics precisely because they considered themselves to be progressive. After all, eugenics had begun to point the way to a bold, hopeful human future through the application of the rapidly advancing natural sciences and the newly forming social sciences to human problems. By investing in the progress and application of these fields, foundations boasted that they could delve down to the very roots of social problems, rather than merely treating their symptoms. Just as tracking physiological diseases back to parasites and microbes had begun to eliminate the sources of many medical ailments, so tracking social pathology — crime, pauperism, dipsomania, and “feeblemindedness,” a catch-all term for intellectual disabilities — back to defective genes would allow us to attack it at its source. As John D. Rockefeller put it, “the best philanthropy is constantly in search of the finalities — a search for cause, an attempt to cure evils at their source.”

In their understanding of themselves, foundations’ determination to reach root causes efficiently and scientifically came to distinguish American philanthropy from mere charity. The old, discredited charitable approach had taken too seriously and had wasted its time addressing the immediate, partial, parochial problems of individuals and small groups. Charity lacked the steely, detached scientific resolve to see through the bewildering, distracting, superficial manifestations of social ailments down to their ultimate sources, which we now had the power to cure once and for all.

Consequently, the first large foundations poured resources into the development and deployment of the natural sciences, as well as promising new social sciences like economics, psychology, sociology, and public administration. Early philanthropists shaped the first major American research universities at Johns Hopkins and Chicago, as well as public policy research institutes like Brookings and the National Bureau of Economic Research, and academic coordinating bodies like the Social Science Research Council.

Alexis de Tocqueville’s idea that America was ennobled by everyday, charitable citizens stepping forward to solve their own problems became less attractive than a new view of social change: objective, nonpartisan professionals and experts could grasp and manage more efficiently and scientifically the complexities of modern industrial life than individuals ever could. Foundation grants would pave the way for this transfer of authority: as one Rockefeller report put it, the foundation’s funding was designed to “increase the body of knowledge which in the hands of competent technicians may be expected in time to result in substantial social control.” Centralized control in the hands of social technicians would require an effort to circumvent and diminish local ethnic, fraternal, and neighborhood groups and charities, which still took their bearings from benighted moral and religious orthodoxies rather than from the new sciences of society.

According to the perspective of philanthropic eugenics, the old practice of charity — that is, simply alleviating human suffering — was not only inefficient and unenlightened; it was downright harmful and immoral. It tended to interfere with the salutary operations of the biological laws of nature, which would weed out the unfit, if only charity, reflecting the antiquated notion of the God-given dignity of each individual, wouldn’t make such a fuss about attending to the “least of these.” Birth-control activist Margaret Sanger, a Rockefeller grantee, included a chapter called “The Cruelty of Charity” in her 1922 book The Pivot of Civilization, arguing that America’s charitable institutions are the “surest signs that our civilization has bred, is breeding and is perpetuating constantly increasing numbers of defectives, delinquents and dependents.” Organizations that treat symptoms permit and even encourage social ills instead of curing them.

Charles B. Davenport, a Harvard-trained biologist, spoke directly to philanthropy’s contempt for charity, along with the former’s yearning to solve problems at their roots. In a booklet published in 1910, Davenport bemoaned the fact that “tens of millions have been given to bolster up the weak and alleviate the suffering of the sick” while “no important means have been provided to enable us to learn how the stream of weak and susceptible protoplasm may be checked.” He insisted that “vastly more effective than ten million dollars to ‘charity’ would be ten millions to Eugenics. He who, by such a gift, should redeem mankind from vice, imbecility and suffering would be the world’s wisest philanthropist.”

Davenport found several wise philanthropists eager to take him up on his proposition to save humanity by funding eugenics. With the help of Mary Harriman, the wealthy widow of railroad magnate E. H. Harriman, Davenport was able to open the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) in 1910, adding it to the Station for Experimental Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor in New York, which had been launched earlier by the Carnegie Institution of Washington. The Rockefeller family and the Carnegie Institution, in turn, added funds to the Eugenics Record Office.

The ERO became a remarkably aggressive and effective institution, skillfully deploying all the available scientific, cultural, and political tools at its disposal to promote its cause. As the top independently funded eugenics institution in the United States, its activities ranged from scientific and policy research, to public education and political advocacy, to training expert field workers whose job it was to track the “stream of weak and susceptible protoplasm” into every nook and cranny of the nation.

Davenport hired Harry H. Laughlin, at the time a teacher of agriculture with an interest in breeding, to manage the ERO. Laughlin became the world’s leading expert on and champion of sterilization. He compiled the authoritative study of its theory and practice; designed a model sterilization statute, variants of which came to be adopted by thirty states; and served as an expert eugenics witness testifying before the congressional committee determined to stem the rising tide of new and defective immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, who were deemed biologically inferior to the earlier immigrants from the northern and western parts. In the notorious 1927 Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell, which upheld the constitutionality of state sterilization laws, Laughlin even provided a deposition confirming Carrie Buck’s feeblemindedness without ever having laid eyes on her.

But philanthropy’s involvement in eugenics went far beyond the success of the ERO. The Rockefeller Foundation helped fund the research institutions in Germany behind the Nazi programs of sterilization and euthanasia. Rockefeller money also supported the work of French surgeon and biologist Alexis Carrel, whose discoveries in vascular suturing earned him the Nobel Prize in 1912. While working at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (today renamed Rockefeller University), Carrel wrote his bestseller Man, the Unknown (1935), which lent his prestige to eugenics, suggested the use of gas to euthanize lawbreakers, and in a later edition endorsed the German “suppression” of “the defective.” The Russell Sage Foundation for two decades employed Hastings H. Hart, a Congregationalist minister-turned-social worker, as a senior official and a consultant; while Hart didn’t support the sterilization of the feebleminded, he was an avid proponent of mandatorily sequestering them.

Somewhat less famous and wealthy donors also had a huge influence on state and local eugenics programs. Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, the co-inventor of corn flakes and a promoter of various causes and treatments that blended theology and pseudoscience, used his fortune to start the Race Betterment Foundation, an organization that promoted eugenics in Michigan and convened some of the first major U.S. conferences on eugenics in the 1910s. In the 1920s, E. S. Gosney, a self-made philanthropist, created the Human Betterment Foundation, which promoted forced sterilization in California and reportedly influenced the Nazi eugenics program. The Charles F. Brush Foundation for the Betterment of the Human Race was founded in 1928 by the eponymous Cleveland inventor and industrialist with the aim of supporting eugenics research in Ohio and around the world. In 1948, several philanthropists, including Procter & Gamble heir Dr. Clarence Gamble and hosiery magnate James G. Hanes, cofounded the Human Betterment League, an organization that pushed for eugenic sterilization in North Carolina. Countless other names could be added to this list.

One of the most interesting tales from the history of philanthropy and eugenics is the career of Frederick H. Osborn. A longtime board member of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Osborn was a president of the Eugenics Research Association and the author of the book Preface to Eugenics (1940), which launched what Time magazine hailed as a new “eugenics for democracy” that America could pursue without fear of being associated with the abuses then becoming embarrassingly evident in the Third Reich. But in the same book Osborn noted approvingly that “the inexcusable process of allowing feebleminded persons … to reproduce their kind is on the way to being checked in a number of states in which such persons may be sterilized.” Osborn was made president of the American Eugenics Society in 1946, and he became the key figure in sustaining philanthropy’s enthusiasm for eugenics after its reputation had been tarnished by the Nazis; he did this by successfully rebranding eugenics as medical genetics and “population control.” In 1952, Osborn joined forces with John D. Rockefeller III to start the Population Council, a group created to pursue many of the same goals as the older eugenics organizations but without the unpleasant odor that had attached itself to eugenics. As late as 1967, when Osborn was in his late seventies, longtime Rockefeller Foundation executive Warren Weaver invited him to write the chapter on “population problems” for an authoritative volume on the history of American foundations. Osborn noted that “we can foresee the time when all over the world the control of births is as much the accepted responsibility of governments as is at present their responsibility for the public health.”

Osborn’s career, and the decades of support he received from American philanthropy, has hardly been given the scholarly and public attention it deserves. Nor have many of the other stories from the history of American philanthropy’s leadership in eugenics. If historians someday succeed in weaving together all these stories into a coherent narrative, I suspect it will be impossible to disagree with Edwin Black’s claim in his book War Against the Weak that eugenics would not “have risen above ignorant rants without the backing of corporate philanthropic largess.”

Does anyone doubt that if eugenics were not now regarded as a moral abomination, philanthropy’s booster squad would be touting it as one of the greatest historical achievements in the advancement of progressive social change? A major Supreme Court decision, over thirty states with sterilization statutes, some 63,000 individuals legally sterilized, millions of potential immigrants who never steamed past the Statue of Liberty — all these would be measurable outcomes sufficient to satisfy the most demanding foundation program evaluator.

Instead, foundations have been notoriously reticent to discuss their role in eugenics, while dwelling endlessly on other initiatives that generally had less impact. On the rare occasions when they comment on eugenics at all, they portray it as an isolated, antiquated misstep on the road to progress. History books about foundations — and there are many, often funded by the foundations themselves — typically don’t have a single reference to eugenics or only briefly mention it to depict it as an aberration, an exception that proves the rule of philanthropy’s otherwise moral success.

It is understandable that foundations would wish to protect their good reputation by downplaying their involvement in eugenics as an early and naïve mistake that should not discredit subsequent accomplishments. This response, however, misses not only that the eugenics movement in the United States lasted for over three decades under philanthropic leadership, but also that the aggressive advocacy of foundations eventually led the U.S. government in the 1960s to implement the eugenics agenda in the developing world in the form of population control programs tied to foreign aid.

There is another approach foundations could take to dealing with sins of the past that doesn’t neglect their weight and their consequences, an approach characterized by research, regret, and reflection.

First, the research: Foundations associated with eugenics should raise a modest sum of money to invite independent scholars to dig into their archives, and locate and publish all the historical documents relating to their involvement with the movement. Three or four leading historians of eugenics could then examine the documents, sum up their findings, and render a judgment about the degree of culpability foundations bear.

There is already a substantial and growing number of historians who specialize in the study of eugenics. The lively production of scholarly and journalistic books on the topic began in the 1960s and 1970s with studies like Mark Haller’s Eugenics: Hereditarian Attitudes in American Thought (1963) and Kenneth Ludmerer’s Genetics and American Society: A Historical Appraisal (1972). The pace of publication has only accelerated, and the publication in 2010 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics is a sure sign that a field of study has established itself and is not going away anytime soon.

This scholarly interest in the history of eugenics makes all the more remarkable the relative dearth of scholarship focusing on philanthropy’s role in that history. Only a handful of books have tried to dig into the historical records in order to tell this part of the eugenics story, like Allan Chase’s The Legacy of Malthus (1977) and Robert Zubrin’s Merchants of Despair (2012). There is no better resource now available on the subject of philanthropy and eugenics than the 2012 expanded edition of Edwin Black’s War Against the Weak. As Black’s footnotes make clear, his account is based on a thorough perusal of thousands of foundation documents. Foundations should move to publish their archived materials on eugenics and should invite historians into their dusty skeleton closets; they owe it to the public, and especially to the victims of the eugenics movement.

Beyond conducting research, foundations involved in eugenics should publicly demonstrate regret. Expressions of remorse by institutions for participation in eugenics are becoming more common, and therefore more expected. In recent years, the governors or legislatures of several of the states that engaged most enthusiastically in eugenic sterilization have issued official apologies. The list includes Virginia (2002), Oregon (2002), North Carolina (2002), South Carolina (2003), California (2003), Georgia (2007), and Indiana (2007). North Carolina has gone further than the other states — first by commissioning a task force to publish a report summarizing the state’s record on eugenics, and more recently by considering legislation that would provide reparations for those victims of the state’s sterilization program who are still alive, amounting perhaps to some two thousand individuals. One of the state’s newspapers, the Winston-Salem Journal, published a superb investigative series in 2002 on North Carolina’s eugenics program and apologized for the enthusiasm for sterilization that a previous generation of its editors had shown. In light of the newspaper’s research, the medical school at Wake Forest in North Carolina also apologized for its role in supporting mandatory sterilization through its medical genetics program — a program that had been funded in part by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, thanks to its indefatigable board member, Frederick Osborn.

But despite dozens of apologies from state legislators and governors, directors of medical schools, and newspapers, not one official public expression of regret has been uttered by representatives of the foundations that helped persuade the states to adopt sterilization laws in the first place. Even to point out the role of philanthropy in eugenics is considered an unfair smear: when I published a speech in 2012 discussing some of the links between philanthropy and eugenics, the top leaders of the Council on Foundations criticized me for “singl[ing] out a shameful piece of global scientific history.” They accused me of deceptively using “an outdated and isolated example” to discredit all of philanthropy’s subsequent wonderful achievements. This was followed immediately by the usual litany of generous, cutting-edge initiatives drawn from various foundation press releases, proving that, in their words, I did not “understand philanthropy’s value as part of a global ecosystem for greater good.”

I confess my acquaintance with the “global ecosystem for greater good” is not all it should be. But I would also suggest that dismissing philanthropy’s neck-deep involvement in the horrors of eugenics as outdated, isolated, and simply what everybody else was doing anyway, is not exactly the response one would expect from the avatar of global goodness.

Let us remember that the state-government officials who apologized for eugenics could simply have said that they were not around when all this happened, and so bore no responsibility. They could have discounted their states’ involvement in eugenics as being commonplace or ancient history. They could have quickly drawn our attention away to all the wonderful things they had subsequently done for the poor and marginalized. Yet they did not. They apologized.

Similar apologies from the philanthropic sector for promoting eugenics are long overdue.

Whether or not regrets are ever expressed, the third component of this approach to handling past wrongdoing — reflection — is imperative. Philanthropy should reflect on what the history of eugenics has to teach us about the dangers posed by the grand projects that seek to drive down to the root causes of social problems and solve them once and for all.

In 2002, Governor Mark Warner of Virginia said on the seventy-fifth anniversary of Buck v. Bell that “we must remember the commonwealth’s past mistakes in order to prevent them from recurring.” Most of the other official state repudiations of eugenics similarly called on citizens to study the past in order to prevent future abuses. Our foundations should be willing to do no less. Very little has changed over the past hundred years in the basic structure of American foundations — the structure that does so much to shield large-scale philanthropy from the consequences of its own actions, including momentous errors like eugenics.

Once a foundation acquires legal status, for instance, no one beyond its own board of directors — which is typically quite small, upscale, and self-perpetuating — has much to say about its ends or means. Prescribed legal supervision by the IRS and by state attorneys general is at best pro forma.

Furthermore, foundations utterly lack the feedback mechanisms that automatically reward or punish other social institutions for their behavior. Foundations do not have to answer to customers or shareholders, as do corporations, nor do they have to answer to voters, as do politicians. Although philanthropy currently professes to pursue more transparency and accountability than it used to have, it is entirely on terms established by foundation management. That is, philanthropy is more than willing to be accountable for all the wonderful things it is doing, which it describes in a stream of relentlessly upbeat press releases and glossy, grin-filled annual reports. But rigorous, honest, hard-hitting journalistic accounts of foundation behavior — the sort of reporting we expect about every other major institution in America — are nearly nonexistent. Foundations remain almost hermetically sealed institutions, more or less impervious to the pressures that push and pull our other economic and political entities, and that make them ever mindful of the consequences of their decisions.

The absence of feedback mechanisms is not the only feature that distances large foundations from public influence. Philanthropies have become ever more professionalized, stratified, and bureaucratic, disconnecting their leaders even further from the concrete social situations they seek to mold.

Their programs are typically staffed by well-credentialed elites, drawn from the most affluent zip codes in the country. Given their social status and academic esteem, it is usually assumed that they are qualified to undertake the boldest and riskiest schemes of social engineering in the name of the global good; that they are able to see well beneath the superficial symptoms of social problems down to their first causes, where they can be fixed once and for all. Happily immune to distorting influences from politics and markets, they are considered to be able to achieve an unbiased and objective view of society’s problems, and to devise solutions that are at once thoroughly rational and coherent, as well as purely public-spirited.

Somewhere far below this sunny upland, however, stands the average citizen, on whose behalf these bold social experiments will be made and in whose neighborhoods they will be carried out. Unhappily, that citizen often seems unable to appreciate the magnitude of the beneficence about to land in his backyard, given his lack of appropriate expertise, his entanglement in everyday, parochial concerns, and the petty moral and religious prejudices that may becloud his judgment.

Every foundation knows, of course, to seek “community input” about its plans. And every foundation knows how to translate that input into resounding community support. If complaints do arise, foundations are tempted to tell themselves that one cannot expect much else from individuals who are able to experience and understand only the superficial symptoms of their own problems, attention to which was the old, discredited approach of charity. Elite philanthropists are prone to think that common folks’ own untrustworthy accounts of their suffering are likely to bear little resemblance to its true explanation, which is accessible only to the penetrating gaze of the trained professional.

It is not difficult to understand how our philanthropic experts can, over time, lose sight of the fact that individuals are not just inadequately self-conscious bundles of pathologies but rather whole and worthy persons, possessed of an innate human dignity that demands respect no matter what problems they may suffer. Once philanthropists have steeled themselves sufficiently to discount the dignity of the suffering person before them in order to pursue a good that the sufferer cannot be trusted to appreciate, they may conclude that the most merciful way to alleviate suffering is to prevent anyone from becoming a sufferer in the first place — by cutting off suffering at its supposed root.

In the case of the eugenics movement, the search for root causes apparently led many philanthropists to conclude that some lives of suffering ought not to have been lived at all. As the British reformer and eugenicist Havelock Ellis put it, “The superficially sympathetic man flings a coin to the beggar; the more deeply sympathetic man builds an almshouse for him so that he need no longer beg; but perhaps the most radically sympathetic of all is the man who arranges that the beggar shall not be born.”

Today, of course, our knowledge of the human genome and our growing capacity to manipulate it present us unparalleled opportunities to see to it that “undesirables” of any sort shall not be born. The fact that we are now able to do so without resort to the crude, messy eugenics of sterilization makes it all the more tempting to view this as a purely scientific act of “radical sympathy.”

As late as 1952, Rockefeller Foundation executive Raymond Fosdick recounted that the foundation’s investments in natural sciences were still guided by the questions it had begun asking in the 1930s, like whether it was possible to “develop so sound and extensive a genetics that we can hope to breed in the future superior men.” The temptation today to genetically engineer the human race is only compounded by the fact that the eugenics episode has been airbrushed almost entirely from the cheerful historical account of American philanthropy. At a moment when we need more than ever to grapple with the subtle moral pitfalls of genetics-driven, root-causes philanthropy, our oldest foundations fail to take seriously their own mistakes. More fundamentally, they seem to ignore that the structure of their organizations, closed off as they are from public input and from the suffering individual himself, provides the conditions that too easily can give rise to the kind of philanthropy that ultimately tears down, rather than builds up, the individual.

In reflecting on its leadership role in eugenics, philanthropy would benefit from thinking of eugenics as its own “original sin,” akin to the Christian concept, or to the way slavery is sometimes referred to as America’s original sin. Philanthropy’s involvement in eugenics should forever remind us that, for all our excellent intentions and formidable powers, we are unable to eradicate our flaws once and for all by some grand, scientific intervention.

Rather, we are imperfect human beings called to compassion and charitable care for other imperfect human beings. Pope Benedict XVI pointed out in his 2005 encyclical Deus Caritas Est (God Is Love) that no matter how just the society, no matter how successful government and, we might add, foundations, may be in bringing about progressive social change, “love — caritas — will always prove necessary.” For “there will always be suffering which cries out for consolation and help. There will always be loneliness. There will always be situations of material need where help in the form of concrete love of neighbor is indispensable.” No state, no mega-foundation can guarantee “the very thing which the suffering person — every person — needs: namely, loving personal concern.”

That loving personal concern is at the heart of charity traditionally understood. It can only be practiced immediately and concretely, within the small, face-to-face communities that Tocqueville understood to be essential to American self-government. There, the seemingly minor and parochial concerns of everyday citizens are taken seriously and treated with respect, rather than being dismissed as insufficiently self-conscious emanations of deeper problems that only the philanthropic experts can grasp.

Pope Benedict’s explanation of caritas reflects a long and noble, if little appreciated, Catholic tradition of standing for personal charity against bureaucratic philanthropy. During the late nineteenth century, even before the rise of the modern foundations, the Charity Organization Society (COS) movement had already launched the trend in humanitarian giving toward rationalization, bureaucratization, and centralization, in the name of what it styled “scientific philanthropy.” Its aim was to organize into a coherent structure and to oversee the many disconnected charities that sought to relieve the plight of the growing number of poor in the nation’s cities. Greater collaboration among individual charities, especially as an attempt to avoid abuse of alms, was indeed a worthwhile goal. But central to the COS movement was also a scathing critique of old-fashioned, unscientific charity as ineffective and duplicative, more likely to produce dependency than to solve problems.

Initially, and not illogically, the Catholic Church viewed this as an attack on the vast network of institutions — workhouses, hospitals, orphanages, and schools — that it had built up in America. Where American Catholicism saw a rich and diverse array of charitable endeavors reflecting every vocation, every need, every tongue, every ethnicity within its swelling ranks, the COS movement saw only waste and redundancy, encouraging rather than curbing poverty — a view later shared by the first major foundations.

Eventually, various Catholic leaders joined local Charity Organization Societies in the interest of neighborly unity with others in a common cause and for the greater benefit of the poor. But Catholics’ emphasis on face-to-face, small-scale charity persisted.

Catholics were all too familiar with views like that of Amos Griswold Warner, one of the leading experts on charity organization, that the church’s network encouraged “widespread mendicity and vagabondage,” and that “distinctively Romanist countries are notorious for the number of their beggars.”

Historian Benjamin Soskis completed a doctoral dissertation in 2010 that brings to light the little-known Catholic charitable counter-movement against centralized professional philanthropy. As Soskis points out, the Catholic Church refused to abandon direct, immediate, voluntary ministry to individual sufferers, or to treat them as bundles of pathology. After all, he notes, “they claimed to view poverty through a supernatural prism and to look upon the indigent as representatives of Christ, to whom Catholics owed a special obligation. Consequently, they worried less about the problem of indiscriminate charity or the specter of pauperism and more about the spiritual damage done to the giver by hard-heartedness or the erosion of sympathy by the forces of centralization and bureaucratization.”

Small wonder, then, that the Catholic Church found little to applaud in the early foundations’ acceleration of the trend toward professionalization and centralization, to say nothing of their enthusiasm for eugenics. It is to the eternal credit of the Catholic Church that, almost alone among the major cultural institutions of the early twentieth century, it refused to yield to the scientific siren call of eugenics. As Pope Pius XI insisted in the encyclical Casti Connubii (On Christian Marriage) in 1930, it is never licit for public magistrates to “directly harm, or tamper with the integrity of the body, either for the reasons of eugenics or for any other reason,” except in the case of punishment for a crime. He condemns those who

by public authority wish to prevent from marrying all those whom, even though naturally fit for marriage, they consider, according to the norms and conjectures of their investigations, would, through hereditary transmission, bring forth defective offspring. And more, they wish to legislate to deprive these of that natural faculty by medical action despite their unwillingness; and this they do not propose as an infliction of grave punishment under the authority of the state for a crime committed, not to prevent future crimes by guilty persons, but against every right and good they wish the civil authority to arrogate to itself a power over a faculty which it never had and can never legitimately possess.

Of course, this sentiment was not shared universally among religious communities, nor even among American Christians; far too many Protestant churches at the time were embracing eugenics as a cutting-edge, scientific way to help establish heaven on earth, as Christine Rosen points out in her fine book Preaching Eugenics (2004). All the while, the progressive movement heaped ridicule on the notion that there were such things as “natural rights” that might stand in the way. But the Catholic Church insisted, in the words of Jesuit Father William Lonergan, that “man has rights which belong to him by nature,” which are “God-given and no Government may ever lawfully and directly rob one of them.” Therefore, “compulsory legislation preventing whole classes not prohibited by nature from marrying is radically wrong and un-Christian.”

Although many Catholic charitable institutions today have become every bit as professionalized and bureaucratized as their Protestant and secular counterparts, others still reflect the traditional understanding of immediate, face-to-face charity. One remarkable example is the worldwide network of communities for people with intellectual disabilities known in French as L’Arche — in English, “the ark” — founded by Jean Vanier in 1964.

Vanier’s approach to the so-called “unfit” is the polar opposite to that of eugenics. Instead of rejecting or seeking to eliminate those who would have once been called the “feebleminded,” Vanier decided to live with them, to love them, and to be changed by them.

The story of L’Arche began when Vanier invited Philippe Seux and Raphaël Simi, two men with intellectual and physical disabilities lodged in a nearby asylum, to come and stay with him in his small cottage in a French village north of Paris. He had no clear plans for how to help these two; he was just going to live in communion with them. But instead of being focused on changing them, he soon realized that they had something to offer to him that would begin to transform him, revealing his own pains and limitations and the fundamental human need for friendship. “I thought I was going to teach them something,” Vanier has said, “and suddenly I was discovering that they were teaching me — quite a bit.”

Vanier soon began purchasing other houses, filling them with both “core members,” as individuals with disabilities came to be called at L’Arche, as well as “assistants,” those who, like him, had dedicated themselves to living in this sort of intentional community. From there, the model spread and there are now over 130 such communities around the world.

Although driven by the Catholic understanding of caritas, L’Arche is designed to bring together the disabled of all faiths, ethnicities, and nationalities. L’Arche challenges the assumption beneath modern progressivism that intellectual prowess should translate into the power to hold sway over others.

As Vanier puts it in his 1998 book Becoming Human, “the social stigmas around people with intellectual disabilities are strong. There is an implicit question: If someone cannot live according to the values of knowledge and power, the values of the greater society, we ask ourselves, can that person be fully human?” That question, Vanier insists, puts far too much emphasis on the priority of reason, the kind of mastering, technocratic reason that is at the core of the progressive project. In asking it, we have “disregarded the heart, seeing it only as a symbol of weakness, the center of sentimentality and emotion, instead of as a powerhouse of love that can reorient us from our self-centeredness.”

To live according to the heart means to open oneself to those on the fringes of society. This does not mean “performing good deeds for those who are excluded,” Vanier explains. Nor does it mean fixing them by getting to the root causes of their problems. It means rather “being open and vulnerable to them in order to receive the life that they can offer; it is to become their friends.” Naturally, being a friend to those who are excluded involves good deeds — providing shelter, food, counsel, or whatever need there may be. But the emphasis in Vanier’s model of charity is less on one-sided giving than on mutual receiving within friendship, predicated on the assumption that both parties offer unique and valuable gifts.

“If we start to include the disadvantaged in our lives,” Vanier argues, “and enter into heartfelt relationships with them, they will change things in us. They will call us to be people of mutual trust, to take time to listen and be with each other. They will call us out of our individualism and need for power into belonging to each other and being open to others.”

As if taking direct aim at the progressive project of imposed rational design, Vanier contends that “the one-way street, where those on top tell those at the bottom what to do, what to think, and how to be, becomes a two-way street, where we listen to what they, the ‘outsiders,’ the ‘strangers,’ have to say and we accept what they have to give, that is, a simpler and more profound understanding of what it means to be truly human.” To those for whom all this sounds far-fetched and utopian, Vanier notes, “if it is lived at the grassroots level, in families, communities, and other places of belonging, this vision can gradually permeate our societies and humanize them.”

The power of that vision fills theologian Henri Nouwen’s posthumous book Adam, God’s Beloved (1997). Nouwen had achieved international renown as a prolific writer and intellectual at Notre Dame, Yale, Harvard, and in his native Holland. His restless search for a vocation beyond the university and his desire to serve the poor eventually led him to Jean Vanier and finally to L’Arche Daybreak in Ontario. It was there that Nouwen came to feel most at home, not least through the friendship and teaching of Adam Arnett, one of Daybreak’s core members. Adam suffered from severe disabilities, including frequent epileptic seizures, and was unable to speak, feed himself, or get about on his own. He would have been Exhibit A in the eugenicists’ portfolio of the “feebleminded” who should never have been born. And yet, here was Henri Nouwen, bathing him, brushing his teeth, and helping him lift his spoon to his mouth each morning.

When one of Nouwen’s friends visited Daybreak, he posed the ever-beguiling eugenic question: “Why spend so much time and money on people with severe disabilities while so many capable people can hardly survive?” he asked. “Why should such people be allowed to take time and energy which should be given to solving the real problems humanity is facing?” But Nouwen insisted that, for him, Adam was not a burden or a distraction. Rather, Adam was — in his utter stillness and silence, in the watchful, holy presence he maintained at the heart of the community — a masterful teacher of patience, compassion, and communal solidarity. Adam “offered those he met a presence and a safe space to recognize and accept their own, often invisible disabilities,” Nouwen wrote. He came to know Adam as a beloved “friend and a trustworthy companion,” discovering that “what I most desire in life — love, friendship, community, and a deep sense of belonging — I was finding with him.”

To claim that Adam had something to teach Nouwen about the heart that far transcended the great intellectual’s prideful reason is truly to stand eugenics on its head. To some of us, it may even sound like mystical nonsense. It reminds us of familiar but still outlandish maxims, like “whoever would be great among you must be your servant,” “the first shall be last,” and especially, “as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.” For Nouwen, Adam brought to life these teachings of Jesus in a way that no abstract doctrine ever could.

But even if we leave overt Christianity out of this account, can we not see that Vanier and Nouwen point us toward a humane alternative to the cold, technocratic rationality of much modern philanthropy? True charity and its embodiment in community may not be just retrograde and ineffective remnants of a previous age. Outsiders, strangers, the poor, and those with disabilities possess an innate human dignity that demands respect, not circumvention. But even more — and this is the truly radical proposition at the heart of L’Arche — they may bear a kind of human wisdom that goes beneath the superficial and evanescent power of reason, right down to the level of the heart. The wisdom of the heart may be able to penetrate to the root cause of suffering in a way that reason never can.

Would it be possible for a foundation to take its bearings from this understanding of charity rather than the mainstream assumptions of scientific philanthropy? It would no doubt be naïve to expect that mega-foundations sitting on billions of dollars and funding thousands of experts could ever be persuaded to abandon the top-down social engineering schemes that have been their trademark since the time of John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie. Nor is it clear how large foundations would make the best use of their resources in a model of face-to-face charity.

But the good news about American philanthropy is that there are some 120,000 foundations in America, most of which are actually quite small. They are often managed by family members or friends of the original donor. A great many of them are governed by charters that limit their giving to a particular city or state.

Such limitations of size and scope may disqualify small foundations from root-cause aspirations but make them ideal vehicles for a genuinely charitable philanthropy. They may not be able to fund ambitious social redesigns, but they can venture out into nearby low-income neighborhoods in search of the sorts of community exemplified by L’Arche. As I discovered during my own years with a foundation in Milwaukee, small charities are everywhere, even in the most distressed and unlikely locales. In battered storefronts, in old fraternal halls, on litter-strewn street corners, they draw the least of these into proud, powerful communities to battle addiction and prostitution, street crime and youth gangs, unemployment and depression.

Those who come to such communities are not treated as passive recipients of professional remedies — typically, the professionals have long since given up on them, and they’ve given up on the professionals. They are treated rather as whole human beings with the responsibility and capability to understand their own problems, and the wisdom to help devise solutions to them. The love and friendship such associations embody, the sense of belonging and purpose they impart, and the wisdom of the heart they cultivate and express bring a degree of healing and wholeness that can never be found with the latest “scientific” fix. They are embodiments of Tocqueville’s understanding of American civil society at its best.

In order to locate and provide proper support for these kinds of communities, grant-makers need to be far more humble and receptive than many of the most celebrated philanthropists have been. For these groups do not have glossy brochures or slick annual reports or dashboards of metrics enumerating outcomes to the third decimal. More than likely they have duct tape on their industrial carpeting and water stains in the ceiling tiles. They will have no professionals on staff, indeed, often no staff at all. So they will not speak the technical jargon of therapeutic intervention, but rather a language of healing and wholeness that veers close to the “mystical nonsense” of Vanier and Nouwen.

Once the grant-maker has found a likely community group, it is important to acknowledge its dignity, its tacit knowledge, and its wisdom by not treating it as a mere vehicle to carry out technical projects designed by the experts. Grants for specific, time-limited projects are not particularly helpful. It is better to provide long-term grants with very few strings attached, acknowledging that those within the association usually know better what the community needs than outsiders. Small foundations should also forgo the mounds of paperwork typically involved in the grant-making process. Instead, they should make personal visits to the group, spending time with those who have benefited from it. They must realize that a community is always hard-pressed to describe in graphs and charts what it does. But it is usually more than willing to invite the honest inquirer into the community to experience its healing presence.

Imbued with the spirit of humility, a grant-maker at a small foundation might be able to open himself to a healing community that could put him in touch with his own inner brokenness. He might find that his job involves more than routinely applying solutions to social problems and that it provides an opportunity for personal growth and fulfillment, a way to himself become more fully human. Any grants made are more than recompensed by the spiritual transformation, the deep friendships in charity, that such communities make available to those open to them.

If American philanthropy can free itself from the hubristic impulse to fix people through abstract, rational schemes, and come to embrace a far more modest understanding of giving based on charitable community, it will have learned the appropriate lesson from the research, regret, and reflection that its involvement in the eugenics episode demands. The changes required are enormously challenging to philanthropy as it now exists, largely unchanged in insulated structure and prideful purpose from its founding a century ago and the era of its original sin. But especially in the new age of genetic engineering, these changes are essential, if philanthropy is to be a blessing, rather than a curse, to the least of these.

During Covid, The New Atlantis has offered an independent alternative. In this unsettled moment, we need your help to continue.