There is mystery behind that masked gray visage, an ancient life force, delicate and mighty, awesome and enchanted, commanding the silence ordinarily reserved for mountain peaks, great fires, and the sea.

The birth of an elephant is a spectacular occasion. Grandmothers, aunts, sisters, and cousins crowd around the new arrival and its dazed mother, trumpeting and stamping and waving their trunks to welcome the floppy baby who has so recently arrived from out of the void, bursting through the border of existence to take its place in an unbroken line stretching back to the dawn of life.

After almost two years in the womb and a few minutes to stretch its legs, the calf can begin to stumble around. But its trunk, an evolutionarily unique inheritance of up to 150,000 muscles with the dexterity to pick up a pin and the strength to uproot a tree, will be a mystery to it at first, with little apparent use except to sometimes suck upon like human babies do their thumbs. Over time, with practice and guidance, it will find the potential in this appendage flailing off its face to breathe, drink, caress, thwack, probe, lift, haul, wrap, spray, sense, blast, stroke, smell, nudge, collect, bathe, toot, wave, and perform countless other functions that a person would rely on a combination of eyes, nose, hands, and strong machinery to do.

Once the calf is weaned from its mother’s milk at five or whenever its next sibling is born, it will spend up to 16 hours a day eating 5 percent of its entire weight in leaves, grass, brush, bark, and basically any other kind of vegetation. It will only process about 40 percent of the nutrients in this food, however; the waste it leaves behind helps fertilize plant growth and provide accessible nutrition on the ground to smaller animals, thus making the elephant a keystone species in its habitat. From 250 pounds at birth, it will continue to grow throughout its life, to up to 7 tons for a male of the largest species or 4 tons for a female.

Of the many types of elephants and mammoths that used to roam the earth, one born today will belong to one of three surviving species: Elephas maximus in Asia, Loxodonta africana (savanna elephant) or Loxodonta cyclotis (forest elephant) in Africa. There are about 500,000 African elephants alive now (about a third of them the more reticent, less studied L. cyclotis), and only 40,000 – 50,000 Asian elephants remaining. The Swedish Elephant Encyclopedia database currently lists just under 5,000 (most of them E. maximus) living in captivity worldwide, in half as many locations — meaning that the average number of elephants per holding is less than two; many of them live without a single companion of their kind.

For the freeborn, if it is a cow, the “allomothers” who welcomed her into the world will be with her for life — a matriarchal clan led by the oldest and biggest. She in turn will be an enthusiastic caretaker and playmate to her younger cousins and siblings. When she is twelve or fourteen, she will go into heat (“estrus”) for the first time, a bewildering occurrence during which her mother will stand by and show her what to do and which male to accept. If she conceives, she will have a calf twenty-two months later, crucially aided in birthing and raising it by the more experienced older ladies. She may have another every four to five years into her fifties or sixties, but not all will survive.

If it is a bull, he will stay with his family until the age of ten or twelve, when his increasingly rough and suggestive play will cause him to be sent off. He may loosely join forces with a few other young males, or trail around after older ones he looks up to, but for the most part he will be independent from then on. Within the next few years he will start going into “musth,” a periodic state of excitation characterized by surging levels of testosterone, dribbling urine and copious secretions from his temporal glands, and extreme aggression responsive only to the presence of a bigger bull, who has an immediate dominance that the young male risks injury or death by failing to defer to. Although he reaches sexual maturity at a fairly young age, thanks to the competition he may not sire any children until he is close to thirty. (Ancient Indian poetry lauds bulls in musth for their amorous powers, even as keepers of Asian elephants have respected the phase as one highly dangerous to humans since time immemorial. Until 1976, it was widely believed in the scientific community that African elephants do not enter musth. This changed when researchers at Amboseli National Park in Kenya were dismayed to note an epidemic of “Green Penis Syndrome,” which they feared signaled some horrible venereal disease — until they realized it was nothing more nor less alarming than the very definition of a force of nature.)

Other than this primal temporary madness, elephants (when they do not feel threatened) are quite peaceable, with a gentle, loyal, highly social nature. Here is how John Donne, having seen one at a London exposition in 1612, put it:

Natures great master-peece, an Elephant,

The onely harmlesse great thing; the giant

Of beasts; who thought, no more had gone, to make one wise

But to be just, and thankfull, loth to offend,

(Yet nature hath given him no knees to bend)

Himselfe he up-props, on himselfe relies,

And foe to none, suspects no enemies.

Donne is not the first or the last to view the elephant in its stature and dignity as a synecdoche for the total grandeur of the universe, come to earth in lumpen grey form. Here he suggests that it represents a moral ideal as well. Animals are often celebrated for virtues that they seem to embody: dogs for loyalty, bears for courage, dolphins for altruism, and so on. But what does it really mean for them to model these things? When people act virtuously, we give them credit for well-chosen behavior. Animals, it is presumed, do so without choosing.

From a religious, anthropocentric perspective, it might be said that while animal virtues do not entail morality for the animals themselves, they reveal to us the goodness in creation; as the medieval theologian Johannes Scotus Eriugena wrote, “In a wonderful and inexpressible way God is created in His creatures.” From a more biological view, it might be noted that people mostly do not choose their dispositions either, that behavioral tendencies are more determined than we like to tell ourselves, and that blame and credit for such things are often misapplied in human contexts too.

But the latter idea — that humans, although capable of conscious self-direction, are as mutely carried along by the force of selection as your friendly neighborhood amoeba — simply elides the question, while the former raises many more; the tiger is as much God’s creature as the lamb. In any case, the capacity for “choosing” is a binary conceit that gestures at something much fuller, an inner realm of awareness, selfhood, and possibility. In other words, a soul.

To the ancients, soul was anima, that which animates, the living-, moving-, breathing-ness of a biological being. In this sense, not only animals but plants have souls (of different capacities appropriate to what they are). For many religions, by contrast, the soul is specifically incorporeal, perhaps immortal, and believed to be unique to human beings, who are responsible (to a point) for its condition. To modern science it is, if anything, the hard problem of consciousness, also commonly thought to be the province of just one species.

Without either choosing sides or somehow reconciling these three dueling realities with each other, it would be impossible to say what a soul is, let alone who has one. But there is a fourth sense in which when we talk about it, we all mean more or less the same thing: what it means for someone to bare it, for music to have it, for eyes to be the window to it, for it to be uplifted or depraved. Even if, religiously, we know by revelation that other people possess them for eternity, we only engage with or know anything about them at a quotidian level by way of the same cues and interactions that a more this-worldly view would take as their sum total: bright eyes, a dejected slump, a sudden manic inspiration or a confession of regret.

Also a matter of conventional wisdom is the idea that human beings are on one side of a great divide while all animals are on the other, subjects of their instincts and our necessities and pleasures. What exactly the divide is, though, is difficult to define. Various contestants have included reason, language, art, technology, religion, walking upright and the use of hands, knowledge of mortality, sin, suicide, and more. In The Explicit Animal (1991), Raymond Tallis rounds up a master list of them:

Man has called himself (among other things): the rational animal; the moral animal; the consciously choosing animal; the deliberately evil animal; the political animal; the toolmaking animal; the historical animal; the commodity-making animal; the economical animal; the foreseeing animal; the promising animal; the death-knowing animal; the art-making or aesthetic animal; the explaining animal; the cause-bearing animal; the classifying animal; the measuring animal; the counting animal; the metaphor-making animal; the talking animal; the laughing animal; the religious animal; the spiritual animal; the metaphysical animal; the wondering animal… Man, it seems, is the self-predicating animal.

As Tallis goes on to explain, any given one of those distinctions is both too narrow, in being an insufficient explanation of what makes human beings human, and too open, in being demonstrably shared to some extent by another species.

Chimpanzees and other large primates, for instance, are so intelligent and personable that they blur many of these boundaries. But since we are so closely connected evolutionarily, it is easy to tacitly view them as way stations toward the human apex, impoverished versions of ourselves rather than somebody in their own right. There is, however, nothing else remotely like an elephant. (Its closest living relatives are sea cows — dugongs and manatees — and the hyrax, an African shrewmouse about the size of a rabbit.) As such, it presents the perfect opportunity for thoughtful reconsideration of the human difference, and how much that difference really matters.

To the elephant, our scrap of consciousness

May seem as inconsequential as a space-invader blip.

In 1974, Thomas Nagel famously took a stab at one of the great riddles of the universe: What is it like to be a bat? To some scientists and philosophers, he noted, this is an unanswerable question; it is not like anything to be a bat because (they believe) the bat does not have enough awareness to subjectively experience itself. Nagel, taking for granted that bats have some kind of experience, also determined that the question is unanswerable because however well we imagine what it would be like for us to live as bats, the bat is so biologically foreign that its experience is beyond our mental grasp.

For people hoping nonetheless to comprehend the lives of elephants, there is an astounding wealth of information about them, a tiny fraction of which appears in the addendum at the end, a slightly larger fraction on my office shelves, and a realistically inexhaustible fund in libraries, databases, and oral histories around the world. The best of these come out of an ethological renaissance kicked off with Iain and Oria Douglas-Hamilton’s Among the Elephants (1975) and continued in such works as Cynthia Moss’s Elephant Memories (1988), Joyce Poole’s Coming of Age with Elephants (1996), Katy Payne’s Silent Thunder (1998), and more, with longitudinal findings compiled in the magisterial volume The Amboseli Elephants (2011). The result of a close-knit, crack team of researchers who have been patiently and creatively observing the same elephant families for decades, this work combines the power of concrete study with the power of story and narrative.

Powerful for us, that is, onlookers from the outside. What is it like to be an elephant? Is it like anything? How would we know?

One of the major clues that elephants have something we would recognize as inner lives is their extraordinary memories. This is attested to by outward indicators ranging from the practical — a matriarch’s recollection of a locale, critical to leading her family to food and water — to the passionate — grudges that are held against specific people or types of people for decades or even generations, or fierce affection for a long-lost friend.

Carol Buckley, co-founder of the Elephant Sanctuary in Tennessee, a retirement ranch for maltreated veterans of circuses and zoos, describes the arrival of a newcomer to the facility. The fifty-one-year-old Shirley was first introduced to an especially warm resident of long standing named Tarra: “Everyone watched in joy and amazement as Tarra and Shirley intertwined trunks and made ‘purring’ noises at each other. Shirley very deliberately showed Tarra each injury she had sustained at the circus, and Tarra then gently moved her trunk over each injured part.” Later in the evening, an elephant named Jenny entered the barn — one who, as it turned out, had as a calf briefly been in the same circus as Shirley, twenty-two years before:

There was an immediate urgency in Jenny’s behavior. She wanted to get close to Shirley who was divided by two stalls. Once Shirley was allowed into the adjacent stall the interaction between her and Jenny became quite intense. Jenny wanted to get into the stall with Shirley desperately. She became agitated, banging on the gate and trying to climb through and over.

After several minutes of touching and exploring each other, Shirley started to ROAR and I mean ROAR — Jenny joined in immediately. The interaction was dramatic, to say the least, with both elephants trying to climb in with each other and frantically touching each other through the bars. I have never experienced anything even close to this depth of emotion.

We opened the gate and let them in together…. they are as one bonded physically together. One moves, and the other shows in unison. It is a miracle and joy to behold. All day … they moved side by side and when Jenny lay down, Shirley straddled her in the most obvious protective manner and shaded her body from the sun and harm.

They were inseparable until Jenny died a few years later.

More stories of kind mentoring in a new home come courtesy of another elephant rescue site, this one in Kenya, where orphans are raised to be reintroduced as adults into the wild. This is a big adjustment, not often attempted for animals who have lived for some length of time in a captive or domesticated setting, but the new releases are helped by older elephants who have gone through the same thing themselves (especially important in welcoming them into a herd that is not their blood kin). In a 2011 report in National Geographic, head keeper Joseph Sauni recounts how an adventurous little one named Irima ran away to try out his independence early. After a few days, a trumpety clamor was heard at the gate. “Irima must have told the group that he still needed his milk and orphan family and wanted to go back,” says Sauni, so Edo, a graduate of the center, walked Irima home. “The keepers opened the gate, and Edo escorted Irima all the way back to the stockades. Edo drank some water from the well, ate some food, and took off again. Mission accomplished.”

Such solicitude is not limited to their own kind. In Coming of Age with Elephants, Joyce Poole tells the story of a ranch herder whose leg was broken by a matriarch in an accidental confrontation with her family. When his camels wandered back without him in the evening, a search party was sent out. He was eventually discovered under a tree, attended by a female elephant who fiercely prevented anybody from approaching. As they were preparing to shoot her, the herder frantically signaled for them to stop. When they were finally able to draw her far enough away for them to go and get him, he explained that

after the elephant had struck him, she “realized” that he could not walk and, using her trunk and front feet, had gently moved him several meters and propped him up under the shade of a tree. There she stood guard over him through the afternoon, through the night, and into the next day. Her family left her behind, but she stayed on, occasionally touching him with her trunk. When a herd of buffaloes came to drink at the trough, she left his side and chased them away. It was clear to the man that she “knew” that he was injured and took it upon herself to protect him.

From whence come these altruistic actions? Are they the product of blind instinct in the animal, the residue of ancestral behavior benefiting kin, whereas for humans they would be a generous and morally commendable choice? Or is the truth somewhere in between, some combination of the two, for both of us? Poole illustrates how the standard framework of evolutionary theory is problematic in describing even highly survival- and reproduction-oriented interactions:

As a behavioral ecologist, I have been trained to view non-human animals as behaving in ways that don’t necessarily involve any conscious thinking and that their decisions have been simply genetically programmed through the course of natural or sexual selection. But in the course of watching elephants, I have always had a sense that they often do think about what they are doing, the choices they have, and the decisions that they are making. For example, when a young musth male is threatened by a high-ranking musth male, his usual response is to drop out of musth immediately. He lowers his head, and urine dribbling can cease in a matter of seconds. Many biologists would explain this phenomenon simply by arguing that males who behave in manner X live to produce more surviving offspring than males who behave in manner Y, and thus the trait for behaving in manner X is passed on to future generations. Thus, male elephants today automatically behave the way they do because they have been programmed through the successful behavior of their ancestors to do so.

It is worth noting that selectively, the decision tree here can go both ways: drop out of musth, avoid the fight, and live to try again another day; or don’t, and make the best play you can to pass your genes on then and there. It is easy to see how either behavior might be rewarded and reinforced by reproductive success over time, either explained just as handily. But the bigger problem is the assumption that in a way, the choice is already determined prior to the interaction, even prior to those two elephants’ births, because as an encoded response there is no room for it to be a choice at all. This automatically excludes a key factor in the scenario, as Poole continues:

Although I rely on such explanations myself, as I have gotten to know elephants better I have been more and more convinced that they do think, sometimes consciously, about the particular situations in which they find themselves. In the case of the young musth male, I believe that he may actually consider his options: to keep dribbling, stand with head high, and be attacked, or to cease dribbling, stand with head low, and be tolerated. In other words, the male may in fact have some conscious control…. With dominance rank between males changing on a daily basis, a male needs to be able to adjust his behavior accordingly. From past experience he knows the characteristics of his rival’s body size, fighting ability, and how that rival normally ranks relative to him, but if his rival is in musth he also needs to assess whether he is in full musth and what sort of condition he is in. All of this information must be assimilated on a daily basis and gauged relative to his own condition. Can so complex an assessment be carried out without thinking? And I wonder whether the more parsimonious explanation wouldn’t be that they think.

Of course, similar mechanistic explanations are now often applied to human actions as well. As Poole acknowledges, they are grounded in something real, but do not allow for the fullest understanding of what is going on. In a way, it may actually be more instructive to look at the flaws in this line of reasoning with an animal example, which helps to avoid some of the metaphysical minefields surrounding the issue. Properly nuanced discussions about animal activity can be soundly materialistic without being reductive. Animal science that describes their real abilities, where they can receive credit for intelligent or compassionate actions driven by more than mere instinct, would by extension elevate man’s stature too — not flatten it with animals’, but raise them both above the low bar of pure determinism.

This moral question is at the heart of Tarquin Hall’s To the Elephant Graveyard (2000), a real-life chronicle of the hunt for a rogue bull elephant that reads almost like a detective novel where nothing is as it first appears. The victim is a drunk man plucked from out of his house and impaled in his own yard. The suspect is a large “tusker” who seems to have sought him out in the village for that express purpose, with no provocation, and has done this to thirty-seven previous victims. A marksman is contracted by the Indian government to shoot the bull and put a stop to this behavior. Hall, a journalist based in New Delhi, believes something fishy is up and finagles his way into the search party so he can expose it.

Sure that Dinesh Choudhury, the marksman, is a stone-cold mercenary insensate to the dignity of elephants, probably framing some meek hapless creature for crimes it could not really have committed, Hall pompously lectures him about them — only to have his pretensions flattened by this man who loves and understands the hathi (elephants) far better than Hall knew was even possible, and who inducts him into a whole hathi universe of deep feeling and sly intelligence and indeed, moral agency.

At one point they catch up with the elephant and Mr. Choudhury steals off to confront him alone — not to shoot, but simply to meet his eyes and give him warning. “I have thrown down the gauntlet. Now the rogue will either mend his ways or I will deal with him,” he explains to an astounded Hall. “If a human kills, he is given a fair trial before sentencing is carried out. Therefore, I always give each elephant a chance to redeem himself. I say to him, ‘If you stay, you will die. If you go, you will live.’” For a man who wants the elephant to take the offer, who hates nothing more than shooting them, it seems an odd profession to go into; but Mr. Choudhury notes that someone would be hired to do it, and “at least with me in charge, the elephant has a chance.”

Having tracked the hathi deep into the northern forest, one night they encounter a legless man who turns out to be his former owner. Many years ago, the man purchased him on a whim, having a lifelong affection for the creatures but not knowing anything about them. Further, being often away from home on business, the owner heedlessly left him in the care of a vicious scamp, returning one day to find him tied up to a tree, malnourished, and scarred from frequent beatings. The keeper (who was nowhere to be found until he was discovered locked up for fighting in a bar) was immediately fired, and a kinder one employed to nurse the hathi back to health. But a few weeks later, the old keeper showed up again, belligerently drunk, demanding money from the owner and taunting the elephant. At the sight of his tormenter, the elephant broke out of his restraints and smashed the keeper to the ground repeatedly, crushing the owner’s legs on the way out.

“I believe the elephant did this to me deliberately,” the owner says. “He wanted me to live in agony. He wanted me to remember him every day for the rest of my life. And so I have done for the past ten years.” The elephant, in those ten years, has ranged all around killing dozens of men in like manner — drunks who resembled his old foe. The owner does not want revenge, he says, because he blames himself for what has happened; but if they can shoot the hathi, he goes on, they “would be ending a lot of pain and misery. Most of all his.”

As a kind of trial, the elephant’s chase poses a question familiar from real trials held in courtrooms every day: how much are violent offenders warped by atrocious pasts responsible for what they do? How relevant is this to what becomes of them, when there is a fundamental obligation to protect society?

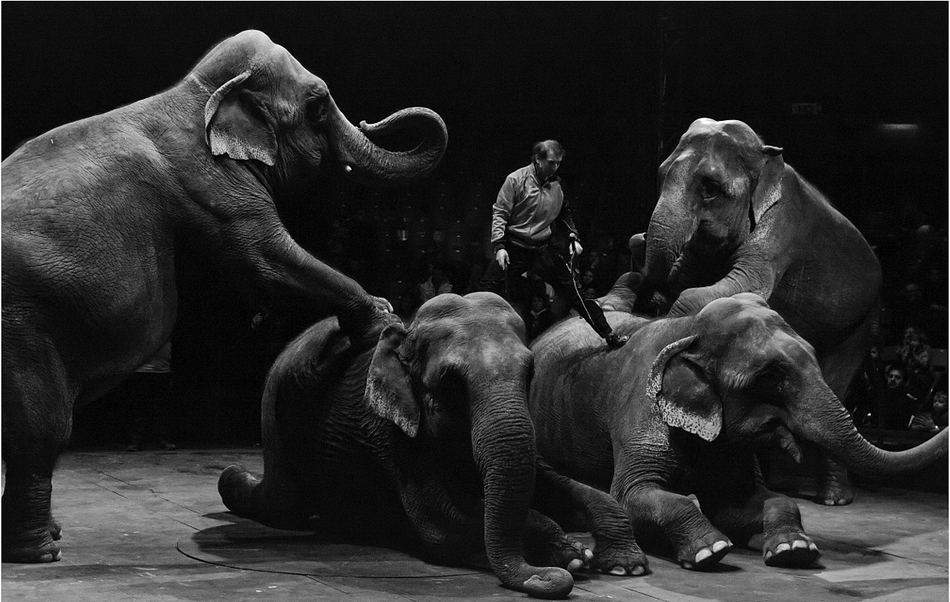

Like humans, most traumatized elephants do not become violent, but just absorb their hurts in confusion and sadness and respond to them in other familiar ways. In The Dynasty of Abu (1962), the zoologist Ivan T. Sanderson recounts the story of an elephant named Sadie, who was practicing but failing to learn a circus routine. Finally she gave up and bolted out of the training ring, causing her to be chastised (not cruelly, he stresses) “for her supposed stupidity and for trying to run away.” At this, she dropped to the ground and dumbfounded her trainers by bawling like a human being. “She lay there on her side, the tears streaming down her face and sobs racking her huge body.”

In almost half a century of close association with the Abu [elephants], including and even after reading a substantial part of the vast literature concerning these majestic creatures, I have not encountered anything that has moved me so greatly, and I write this in all seriousness and humility. Its ineffable pathos constantly brings to mind that most famous verse “Jesus wept” (John 11:35). What on earth are we to make of a so-called “lower animal” crying?

If you shoot an animal, you may expect it to make whimpering noises…. That any animal, and especially one weighing 3 tons, should lie down and sob her heart out in pure emotional frustration is something else again. It almost looks as if, despite all that we like to believe, we humans are not the only creatures that possess what we call emotions and higher feelings. In fact, if we insist upon making a distinction between ourselves and other animals in this respect, we will then have to provide a special niche for the Abu.

In Charles Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals — an 1872 work that, together with The Descent of Man (1871), applies the principles of evolution to the question of human origins — elephants appear twice: briefly in a note on the way their ears flare when they charge each other for a fight, and more extensively with an inquiry into the phenomenon of captive elephants weeping. Darwin reports the observations of a colonial secretary in Ceylon (Sri Lanka): “When overpowered and made fast, [one newly captured bull’s] grief was most affecting; his violence sank to utter prostration, and he lay on the ground, uttering choking cries, with tears trickling down his cheeks.” Others, meanwhile, simply “lay motionless on the ground, with no other indication of suffering than the tears which suffused their eyes and flowed incessantly.” A zookeeper in London, Darwin adds, witnessed similar occurrences whenever his companion pair of cows were split up. Ever the painstaking naturalist, Darwin latches onto a physiological investigation of the muscles surrounding the eyes — how their contraction may cause or allow for tears, whether they are more likely to be contracted while prostrate, and so forth. He manages to induce a batch of children to squeeze these muscles repeatedly as a test, to very little tearful effect.

We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. Remote from universal nature, and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time.

Though thanks to Darwin (if not Aristotle) it should come as no surprise that animals seem to experience in some way many of the same things we do, physically and emotionally, in science the supposed imposition of “human” characteristics on non-human animals is a powerful taboo. All of the preceding stories, descriptions of behavior whose meaning would be perfectly obvious if encountered in a person, court trouble with sticklers for “romanticizing” the animals’ apparent feelings.

In Love, Life, and Elephants (2012), Daphne Sheldrick — founder of the orphanage mentioned above, and inventor of the first successful milk substitute for infant elephants — describes her involvement in writing articles about animal behavior for the Wildlife Clubs of Kenya’s schools, and how to her dismay so much of the literature she read for this assignment turned out to be abstruse and off the mark as compared with her and her colleagues’ field experience:

I attributed this to the fact that science precluded researchers from interpreting animal behavior in an “anthropomorphic” way, and as such they came up with complicated explanations as to why an animal was behaving in a certain way, when, in fact, the answer was pretty simple. One simply had to compare it to the likely response of the human animal if subjected to the same set of circumstances.

Researchers are not even supposed to name their subjects, lest the sense of intimacy in a name compromise their objectivity. The primatologist Jane Goodall was among the first to revolt from this convention, and now most elephant ethologists go ahead and name their subjects too; as Iain Douglas-Hamilton has said, “even if you identified an elephant by the number M51, when you saw him coming your way, you would still say to yourself, ‘My God, it’s M51!!!’”

Indeed, Douglas-Hamilton’s remark speaks to the very reason why scientists worry about mixing human feelings into animal research: it’s practically irresistible. Scientific observation is supposed to be detached, but science after all is conducted by human beings, and human hearts naturally reach out to other sentient creatures; perhaps our affection for them makes us want to see what isn’t there.

Despite its limits, surely this is a better orientation than that of the British Raj officers of yore, who in the great tradition of Royal Society vivisections and other such doings obtained a wealth of information about elephantine physiology by restraining the animals and applying pain to find the most sensitive pressure points, coldly taking notes on their new knowledge of the nervous system. But the dilemma remains: how to get an accurate understanding of the animals’ nature and (if appropriate) emotions, without imposing on them assumptions born of a distinctly human understanding of the world?

The taboo against anthropomorphism exists for three basic reasons. First of all, we as human beings are prone to mistake the thoughts and feelings of each other, even the people we are closest to — how much more so is this a risk in speculating about members of another species?

Even supposing that the elephants were our equals in intelligence, their life differs from ours so fundamentally that trying to infer their perspective from our own experience is bound to miss the mark in many ways. For one thing, as a rule elephants have poor vision — but their sense of smell is exquisite, revealing a whole olfactory landscape that we are contentedly closed off to. Also, they do not fall romantically in love (that we know of; that their behavior indicates). Think how many other aspects of our lives are profoundly influenced by good sight and deep eros, and ask yourself what might loom equally large in an elephant’s world that we ourselves would have very little grasp of. And of course there are a variety of other differences — where they live, how they live, the fact that from birth to death a female (unless something has gone wrong) will never be alone and after a certain point a male mostly will. How might these things shape a psyche?

Meanwhile, on our end, we the human race are masters of projection, from the teddy bears (or in my case, stuffed raccoons and walruses) that we befriend as children to the humanoid robots that we may build or purchase as adults, engineered to cue us to respond to them like sentient beings. We like to feel that these inanimate objects have reciprocal affections for us, although we always know at some level that they do not.

For real sentient beings, though, the truth is more complex. They are not us, but to look into their eyes is to know that someone is in there. Imposing our own specific thoughts and feelings on that someone is in one sense too imaginative, in presuming he could receive the world in the way we do, and in another not imaginative enough, in not opening our minds to the full possibilities of his difference. The philosopher and theologian Martin Buber called this “the immense otherness of the Other,” reflecting on his relationship with a family horse as a child. As he stroked the mane, “it was as though the element of vitality itself bordered on my skin” — “something that was not I,” he notes, but was “elementally” in relation to him. There was an existential connection between them in their improbable blessing of breathing, beating life. And not only life, but the particularity of sentient individuals, as the horse “very gently raised his massive head, ears flicking, then snorted quietly, as a conspirator gives a signal meant to be recognizable only by his fellow conspirator: and I was approved.”

Of course, there is no way to know what the horse was really thinking here. But as to what Buber was thinking — notice how he moves from their shared primal vitality, realized by touch, to their distinct seats of awareness, and the possibility of coming together in faux conspiracy. Consider how any empathetic connection forms. You begin with some point of commonality with your own life, something as elaborate as a similar identity or experience or as simple as a feeling everybody knows firsthand, such as pain or affection. From what is same, however basic, you can begin to bridge the difference to what is other, and learn something new through someone else’s eyes.

This leap will always involve some element of imagination, as we cannot know exactly what someone may be feeling on the other side. Thus our empathy and irrepressible imagination are not merely impediments to clear understanding, but may instead offer new avenues toward it.

The second reason for the taboo is that in modern Western science, the whole concept of life is so mechanical that, if you look closely, not even people are supposed to be anthropomorphized. Emotional, holistic terms such as love, sorrow, and concern have no place in an impoverished language of chemical transactions at the micro level and selection pressures at the macro. Not that chemical transactions and selection pressures are not essential influences, because of course they are — but from our current knowledge of them, they are acutely inadequate to describing the subtleties of lived experience.

This framework goes back to Descartes, whose dualistic universe of absolute mind at one end and absolute matter at the other admitted nothing in between. Indeed, Descartes reasoned that since animals are not rational, they are not conscious, and since they are not conscious, they cannot even be aware of pain; their piteous howls during the horrible experiments he conducted on them were to him mere reflex, the unfelt expression of material reactions akin to the shrieking of a teakettle.

This idea was long ago debunked, but the philosophy it came from lives on in various ways. Early developers of artificial intelligence, for instance, focused on programming mightily rational functions such as chess and advanced mathematics — tasks that are ideally suited to computers, but also, as M.I.T.’s Rodney Brooks quips in Flesh and Machines (2002), that “highly educated male scientists found challenging,” which therefore must be the pinnacle of cogitation. In fact, Brooks realized, while “the things that children of four or five years could do effortlessly, such as visually distinguishing between a coffee cup and a chair, or walking around on two legs, or finding their way from the bedroom to the living room were not thought of as activities requiring intelligence,” they represented the real challenge for programming. Never mind small children — there is not a robot in the world that knows the things a puppy knows.

In a 1990 paper serendipitously titled “Elephants Don’t Play Chess,” Brooks observes that evolutionarily, “the essence of being and reacting” — that is, “the ability to move around in a dynamic environment, sensing the surroundings to a degree sufficient to achieve the necessary maintenance of life and reproduction” — was a far more difficult development than reason-centered capabilities, as impressive as they are. More importantly, the latter emerged in continuity with the former, not as a detached occurrence with an unrelated meaning.

This is an important corrective to the abstraction of thought from embodiment, and ought to indicate that mental and emotional experiences we know we have might well be shared to some degree by fellow creatures, our evolutionary kin; discerning them is not imposing human attributes on animals but just acknowledging the results of a common heritage.

To be sure, this field comes with its own pitfalls, the retroactive just-so stories that speculatively explain the evolutionary heritage of any behavior, as Poole discussed above. But in any event, today we have readmitted into respectable science a whole spectrum of biologically-based feeling, though this is actually because we are leaving behind the mind for just the matter. Pure conscious rationality, instead of the one sure thing, is by some accounts an elaborate delusion. That is a subject for another time, but for here and now the lesson of Descartes is this: to deny obvious suffering based on a preconceived idea is as unscientific as it is heartless. Believing that the appearance of boredom, loneliness, frustration, and grief in animals is simply an anthropomorphic projection is to labor under a forced ignorance that is protested by our own intuition as well as all the evidence. Even as new developments offer more insight into the distinctions between their feelings and ours, we have to grant the benefit of the doubt that they are feeling something.

A third objection comes not out of science but from culture and politics: the idea that acknowledging even faintly human-seeming qualities in animals will ultimately serve not to affirm the moral worth of animals but to debase the worth of human beings. The example of Peter Singer shows that this fear is not unfounded. Singer’s classic 1975 manifesto Animal Liberation is a passionate call for the protection of feeling animals, and in many ways the founding document of the animal advocacy movement. (He eschews “rights” talk, although this has mostly been lost on his followers and critics alike.)

But Singer is equally well known for promoting reprehensible ideas about the treatment of vulnerable human beings — the young, the old, the ill, and the disabled. The insidious connection between these two stances is a philosophy that attaches value to specific capacities rather than beings as a whole: If a certain level of intelligence or other properties means animals should be accorded more value, conversely, to Singer the absence of those properties in some people makes those individuals worth less.

In contrast to this kind of utilitarian, à la carte moral value, there is a kind of animal advocacy that promotes a radical leveling of species: as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals founder Ingrid Newkirk famously said, “When it comes to pain, love, joy, loneliness, and fear, a rat is a pig is a dog is a boy.” While Newkirk grounds her claim in core emotions (which all those species do have), others take the position to what they see as its logical conclusion, equating any kind of life with any other — a spider, a bacterium, a child — a concept whose practical implications must either be nonexistent or paralyzingly exhaustive.

Though based on nearly opposite standards for how to value living beings, both these approaches basically annihilate human equality as a special ideal, that self-evident truth that somehow in all times and places has been shockingly hard to defend. Hence valiant crusaders against assaults on this front, such as bioethicist Wesley J. Smith (author of a 2010 book titled after Newkirk’s statement), smell danger in any discussion of animal sentience and emotion. Think of the beautiful stark simplicity of the “I Am a Man” banners carried in the civil rights marches; what if, instead, they said “I Am an Organism,” whose rights are either contingent or unenforceable? This is the moral universe that people suspicious of animal advocacy fear.

Animal welfare, rather than animal rights, is the proper locus of our concern, they seek to remind us (Smith commonly makes this distinction throughout the book and in his blogging and articles about “human exceptionalism”); it is not the animals’ stature as living beings but ours as moral agents that obligates us to relate to them kindly. Whatever the philosophical merits of this stance, it is certainly true at a practical level that people have power over animals in most situations and so it is up to us to set the standard for their treatment.

So what does animal welfare entail? One approach is outlined in Dominion (2002), Matthew Scully’s rigorous critique of various industrial and sporting practices based on known evidence of animal sentience and emotion — a straightforward if gruesome argument not that we are offending our equals but that we are failing our dependents.

On the other hand, it is hard to say what Smith considers an acceptable limit on human needs and desires when balanced against animals’. He characterizes Scully’s book as “outrageously anthropomorphic,” and describes some of the writings of Jane Goodall, the world’s leading animal scientist, as “pure figments of [her] imagination”; Goodall “almost screeches as she anthropomorphizes away.” In Smith’s view, Scully and Goodall go wrong by inferring emotional states from animals’ observable behavior. Smith also criticizes an elementary-school primer on farm animals as “propaganda,” not only for the admittedly ridiculous inclusion of the names of vegan celebrities, but also for “anthropomorphically aimed” items such as this: “Cow Fact: Mother cows separated from their calves by a fence will moo loudly and seem very upset. They’ll wait through hunger, cold, and bad weather to be with their calves.” Smith does not dispute that the mooing actually takes place; if there is anything about animal psychology that would seem to be pretty well established, it is mothers’ attachment to their young. But apparently the suggestion that this behavior indicates the presence of recognizable emotions is a dangerously anthropomorphic idea to be putting in the heads of children.[*]

Denying the obvious is a bad way to go about promoting causes, even (or especially) very good ones. And the emphasis on human exceptionalism — as Smith asks, “What other species builds civilizations, records history, creates art, makes music, thinks abstractly, communicates in language, envisions and fabricates machinery, improves life through science and engineering, or explores the deeper truths found in philosophy and religion?” — in a vein that Raymond Tallis calls “a misconceived, panic-stricken desire to preserve human dignity by distancing man from the animals,” somewhat misses the point.

Ingrid Newkirk does not claim that rats and pigs can make machinery or ponder metaphysics, but that they feel emotions, and that taking those into account, we should not degrade or harm animals in the ways that matter to them — not by being denied suffrage, say, but by being bored or scared or separated from their families. Their worth need not be pegged relative to anybody else’s to acknowledge this.

For that matter, Smith’s line of argument serves to undermine his more important point. The vulnerable and disabled people whom he spends most of his time fighting to protect are themselves often unable to do a good portion of the exceptional things he praises — which is just the sort of limitation that causes Peter Singer and his crowd to question their “personhood.” Arguing from the height of human activity may not be the most persuasive way to make the case for those who cannot hope to reach that height.

On the other hand, as these capacities do have a bearing on the stature of the species overall, it ought to follow that other species with heightened abilities should be accorded value for those things as well. In any case, tactically speaking, one would think that sensitivity and respect for life at different levels would find themselves in common cause. We can all recall examples from human history in which people’s natural sympathies towards others, whom they knew deep down to be like them, were closed off by feats of ideology — and of still more examples where the baseline of those natural sympathies left much to be desired. Our natural sympathies represent an invaluable kind of moral insight to be nurtured rather than squelched wherever they do appear. Without establishing equality per se, this surely applies to our relationship to animals as well.

Staff members at the Elephant Sanctuary told me of an incident with one of their “girls,” who spotted a fallen bird outside her barn and ran right over to it, utterly distraught. She crooned and stroked it and did not settle down till it had been properly laid to rest. What did this mean to her, exactly? We don’t know. But she was clearly very moved by a fellow creature’s woe and had no trouble seeing it for what it was, different life forms though they were. How sad when we, “higher” animals who share this gift, convince ourselves to dull it.

“Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? And not one of them will fall to the ground apart from your Father. But even the hairs of your head are all numbered. Fear not, therefore; you are of more value than many sparrows” (Matthew 10:29-31). If a single little bird is worth the all-consuming grief of Dulary the Elephant and the cosmos-animating mind of the Father of Creation, and human worth surpasses that, then what is there to lose in holistically appreciating the life of this one bird, even insofar as it resembles ours? And how much more than the bird an elephant, which by its own extraordinary nature shows that all species are not equal — but is a portal to the world of non-human life, and the possibilities therein.

The proper study of mankind is man, but when one regards the elephant, one wonders.

If the core elements of life, sensation, and emotion are so widely distributed as to encompass a huge swath of the animal kingdom, what is the moral difference between a species with higher capabilities and one without? In his thoughtful 1985 essay “Tool, Image, and Grave,” the philosopher of biology Hans Jonas takes up three activities attributed solely to humans and explores their deeper implications. As it happens, given what we know today, elephants arguably meet all three tests. Jonas’s standard is worth revisiting in this light — not to diminish its significance for Homo sapiens, but to consider what it means for the one other animal, at least, that might share it.

Jonas selects these particular traits on the basis that they are known to have existed even in prehistoric man, and even in their most incipient forms are indicators of important mental and spiritual qualities that would seem to make him unique. The first example is the tool, which Jonas notes is “very closely connected with the realm of animal necessity.” And yet, a tool is an artificial construct, not an extension of organic action but a separate object, often crafted with another object, and most importantly necessitating a concept of what it and its purpose will be in order to be crafted.

On one count, elephants fail the tool test, for they do not make artifacts they then reuse (and obviously have not developed the kind of technology that has completely unleveled the odds in our efforts to hunt or trap or train them or encroach upon their habitat). However, they do use objects as intermediaries between them and their environment, such as sticks to scratch between their toes and remove bugs from other areas, or twisted clumps of grass like Q-tips to clean inside their ears or whisks to swat at flies. As J. H. Williams recounts in Elephant Bill (1950), work elephants in Asia collared with bells have been known to plug up the bells with mud so that they can go and steal bananas in the middle of the night unnoticed — a purposeful modification of someone else’s tool. Elephants dig holes for water, cover them with plugs of bark and grass, and return later to their secret stash. Elephants learn by trial and error what sorts of materials do and do not shock them in their efforts to break through electric fences — and in at least one recorded instance (described in Lawrence Anthony’s The Elephant Whisperer [2009]), followed the buzzing of the fence all the way around to its origin, the generator, which, having been stomped to smithereens, allowed them to untwine the fence and go their merry way.

All these behaviors are oriented directly toward fulfilling basic animal wants and needs, and all are similar to the kind of instinctual modification of self and surroundings — hoarding, nesting, sneaking, grooming — that any animal does to survive in the world. The sophisticated actions that animals carry out thanks to the instructions of “instinct” are really quite amazing, and difficult to comprehend for we who rely so much more on conscious reasoning; how much does the animal “know,” and how can it do what it’s doing if it doesn’t? In any case, these complex elephant behaviors would seem to show a great degree of intelligence, an awareness of cause and effect, and some grasp of the multiple possibilities inherent in the properties of their surroundings — that is, what Jonas calls the power of imagination, a grander power than the cold (though equally applicable) contemporary phrase “high cognitive capacity.”

Jonas’s second example, image-making, is a capability which “displays a total, rather than a gradual, divergence from the animal’s.” The activity is biologically useless, he notes, and requires sufficient mental abstraction to distinguish between reality and representation — that is, between the sensations of the present moment that all animals experience and the form of something else in memory or the imagination. Image-making is the transference of this metaphysical idea onto a physical substrate; even for a portrait or some other picture modeled on something real and present, the copy is distinct from the original but linked to it by a nonmaterial concept.[1]

It is worth noting that making images as well as tools depends on not only sufficient mental abstraction, but more practically hands, or some kind of hand-like appendage, such as a trunk, something that allows for a special kind of active engagement with environs. In fact, given their prehensile facility, elephants can be trained to make representational paintings — of flowers, balloons, and elephants, mainly — just as they can be trained to perform many other sophisticated tricks. (Given their intense boredom in captivity, where almost any activity can be appealing, it is not only a crowd-pleaser but seemingly fun for the elephants, whose work is then sold to fund their care and other conservation efforts, otherwise known as win-win-win.) Some elephants, however, make art of their own accord — mostly, as it appears, abstract, but some bordering on representational. Ruby, who spent almost her entire life at the Phoenix Zoo and was given paints for recreation after her keepers observed her always doodling in the sand, would commonly select paint colors that matched events around her, such as visitors’ shirts outside her cage or the red, yellow, and white of a fire truck that had pulled up with flashing lights earlier in the day.

The best documented example, however, is Siri of the Rosamond Gifford Zoo in Syracuse, New York, who was observed in 1980 by her keeper to be drawing with a pebble on the floor of her enclosure — all alone, often at night, entirely of her own volition. The most striking of these markings was a little design that looked for all the world like the Chinese character for Buddha; the keeper, David Gucwa, bestowed on it the cheeky and evocative title “To Whom It May Concern,” and from that point on began to supply her with paper and pencil. He would sit quietly with sketch pad in his lap and pencil sitting nearby, and without any prompting or guidance Siri would draw.

Many of the drawings — collected in a lovely 1985 book titled after that first etching, cowritten by Gucwa and reporter James Ehmann — actually do somewhat resemble corporeal entities: a butterfly, a bird, a person. This is likely happenstance, though; by and large the drawings are much more emotionally than rationally expressive. Be that as it may, clearly there was something in Siri’s inner life she felt compelled to bring forth. The question of what to make of it is a revealing example of the cryptic expanse between the intent of the artist and the significance to viewers.

To some, of course, the whole thing is simply a send-up of the very concept of modern art — “people today pay money to acquire stuff that I would pay money to get rid of,” carped one biology professor sent a packet of Siri’s work for comment. On the other hand, on being shown the drawings two senior zookeepers immediately resolved to go vegetarian, blown away by this glimpse into an uncharted realm of animal psyches. “I don’t even step on spiders anymore,” one said, “and I don’t like spiders. Nothing is simple anymore.” Stephen Jay Gould called the portfolio “fascinating” but cautioned, “I have a hard enough time assessing my own motivations; Lord only knows what goes on inside the brain of an elephant.”

Art scholars, for their part — more content than scientists to coexist with endless ambiguity, and indeed to revel in just that kind of clue into the deep unknown — were universally enthusiastic, all remarking on the energy and lyricism and even joy, and affirming certain spatial forms and techniques that indicated the work was more than merely random scribbling. Like the prehistoric cave paintings Jonas points to, it is a creative message defying both meaninglessness and easy understanding, calling across improbable distances of time or consciousness or species to whomever it may concern.

Incidentally, in an entirely different kind of “image test,” elephants are distinguished as well: they can recognize themselves in mirrors. Very few other animals have been shown to do this, mainly dolphins and great apes. The test is performed as follows: While the animal is unconscious, some part of its anatomy out of its range of vision is marked with odorless paint, and often for control a corresponding location is marked with a clear version of the paint. When presented with a mirror wherein the mark is reflected, it turns to that location on its own body to explore it, indicating both self-awareness and an understanding of the meaning of the mirror. Human beings begin to pass this test at about eighteen months of age.

Jonas’s final and strongest criterion is the grave, which would seem to separate man from animal unambiguously. The “commemoration of the dead perpetuated in the cult of the grave” bespeaks an awareness of mortality that is the foundation of metaphysics: “in considering ‘the afterwards’ and ‘the there,’ [man] also considers ‘the now’ and ‘the here’ of his existence — that is, he reflects about himself. With graves, the question takes on concrete form: ‘Where do I come from; where am I going?’ and ultimately, ‘What am I — beyond what I do and experience at a given time?’” For man, his sense of self, sense of history, and sense of the intemporal, however inchoate, are gestured at with his remembrance of those who have passed on.

But here he is joined by the elephants, the only other known creatures that — whatever it may mean to them — purposively commemorate their dead, in a way Joyce Poole calls “eerie and deeply moving”: “It is their silence that is most unsettling. The only sound is the slow blowing of air out of their trunks as they investigate their dead companion. It’s as if even the birds have stopped singing.” Using their trunks and sensitive hind feet, the ones they use for waking up their babies, “they touch the body ever so gently, circling, hovering above, touching again, as if by doing so they are obtaining information that we, with our more limited senses, can never understand. Their movements are in slow motion, and then, in silence, they may cover the dead with leaves and branches.”

After burying the body in brush and dirt, family members may stay silently with it for over a day; or if a body is found unattended by elephants not related to it, they may pause and stand by for some time. They do this with any dead elephant, recently deceased or long departed with only the skeleton remaining. “It is probably the single strangest thing about them,” Cynthia Moss writes:

Even bare, bleached old elephant bones will stop a group if they have not seen them before. It is so predictable that filmmakers have been able to get shots of elephants inspecting skeletons by bringing the bones from one place and putting them in a new spot near an elephant pathway or a water hole. Inevitably the living elephants will feel and move the bones around, sometimes picking them up and carrying them away for quite some distance before dropping them. It is a haunting and touching sight and I have no idea why they do it.

Understandably, for many years it was rumored that elephants had designated graveyards. This has proved essentially untrue, although their skeletons often do collect in the same place, such as near a water hole, where the ailing and elderly tend to stay towards the end of their lives — and as Moss notes, sometimes do get moved around. The mother of a dead baby may drape it over her tusks and carry it with her for days, if she is not standing vigil.

Elephants even react to carved ivory, long divorced from the original remains and altered and handled extensively. Poole writes of a woman who came to visit Tsavo National Park wearing ivory bracelets: as an elephant approached, the park warden cautioned her to hide them behind her back; but when the elephant arrived, she reached around behind the woman and contemplatively perused the bracelets with her trunk. Poole then had a friend stage a repeat performance later, and the same thing happened. Conversely, elephants have also been observed to become quiet and pensive in an area where relatives died, even years ago, although the bones have long been removed.

While elephants are unfailingly interested in the remains of their own kind in whatever form, they have occasionally been known to bury dead rhinos, lions, and humans as well. In some cases, the people were only sleeping, and awoke to find themselves trapped under enormous heaps of foliage. Other times, they have been injured or paralyzed with fear by a furious elephantine rampage, which came to an abrupt end when the elephant perceived them lying still on the ground, and switched in an instant from ferocious self-defense to solemnly performing its rites for the dead.

“Creatures, I give you yourselves,” said the strong, happy voice of Aslan. “I give to you forever this land of Narnia. I give you the woods, the fruits, the rivers. I give you the stars and I give you myself. The Dumb Beasts whom I have not chosen are yours also. Treat them gently and cherish them but do not go back to their ways lest you cease to be Talking Beasts. For out of them you were taken and into them you can return.”

For those who find this type of evidence sentimentalized, dubiously interpretable, or otherwise unsatisfactory, there are various nice solid measurements that provide useful but crude indicators of elephants’ relative intelligence. At birth, an elephant brain is about a third its adult size. A human brain at birth is a quarter its adult size, whereas for chimps it is half and for most mammals the figure is more like 90 percent. A greater span of growth outside the womb like this accompanies a more important role that nurture and learned skills play in the animal’s maturation — as infants they are more helpless and dependent than an average mammal, but as adults there will be much more that they can do. The elephant brain is also notable for its high level of spindle neurons (associated with sociability), very large temporal lobes and hippocampus (the primary seat of memory processing), and convoluted neocortex (linked to general cognitive complexity, common to other intelligent species such as dolphins and higher-order primates).

But when you ask what these things mean as lived, as translated into capabilities and actions, you find yourself back in the mushy territory of observing quasi-mythical or very-human-seeming behavior and trying to analyze its significance from the outside. And in the category of things you might be prone to romanticize, at the very top there is a faculty that also tops the list of features supposed to distinguish man from animal — and that could, if properly deciphered, unlock the rest of elephant experience for us in a way nothing else will. “The Romans fancied that the elephants had reason, and understood the language of men, though they could not answer them,” the nineteenth-century historian John Ranking observed. The Romans were not alone. What elephants may be lacking most of all is not language but the Rosetta Stone to prove they have it and clue us in to what on God’s green earth they’re talking about all the time.

Animal communication is a tricky subject. Even comparatively lowly critters have mind-boggling ways of signaling information to each other. Bees, to convey to other bees the location of home or food or some other desired destination, perform a “bee waggle dance” that simulates the directions in scaled-down form — and there are different “dialects” for this choreography as practiced by the same species in different regions of the world. A mother bat returning to the cave with food for her little one can somehow instantly pick out his specific cheeping from the thousands of others huddled on the wall. There is even just the detailed social profile of all the neighbor dogs your pet checks out from sniffing hydrants on his walk.

However, this sort of thing does not necessarily rise to the level considered worthy of the label “language” — though determining where that level should be is hard to say. Even taking into account the impressiveness of all these forms of interchange, and the fact that there is much about them yet to be discovered and explained, we risk defining the term out of its useful meaning if we stretch it to encompass so much that human (or humanlike) powers of complex abstract discourse cease to be recognizably extraordinary.

“Since time immemorial [speech] has been correctly acknowledged to be man’s most outstanding trait,” Jonas wrote (though not addressing it in his own essay). There is an intricate philosophical link at least in the Western tradition between language and beliefs and choices, and thus moral reasoning and self-determination. (Cultures with a higher general estimation of animals than ours may not precisely share this view, or may just accept that animals have language that is obscure to people. It is interesting to consider how the everyday proximity to different kinds of creatures may have affected the development of these beliefs. That is, elephants, higher-order primates, and the like are not native to the West, and thus our basic common sense of what “animals” can think or do calibrates at the level of, say, horses and dogs — not to malign the intelligence of horses and dogs, which we tend to underappreciate anyway. But in Asia and Africa, where there’s been much more natural interaction between people and very smart animals — and not as novelties but as members of other communities — most cultures seem to take a more expansive view of animal potential.)

For a careful analysis of the language question from the Western philosophical perspective, the interested reader may turn to virtue ethicist Alasdair MacIntyre’s Dependent Rational Animals (1999), which walks through the discussion on this point while focusing especially on the example of dolphins. Reminding us that “much that is intelligent animal in us is not specifically human,” MacIntyre goes to battle with some residual Cartesian silliness, and takes care (as many philosophers have not) to locate animals on a spectrum of higher and lesser intelligence — a dog, for instance, may have more in common with a person than with a crab in most significant respects — drawing out the implications at each stage till he arrives at conscious action.

A more distilled, whimsical presentation appears in C. S. Lewis’s allegorical world of Narnia, with the contrast between ordinary creatures and the “Talking Beasts.” Their animal natures give them certain innate qualities — steadfastness in a bear, valor in a horse — but their speech gives them control over their animal instincts by the powers of thought and self-direction it endows. They are the moral equals of human characters because of this, and anyone who treats them as equivalent to ordinary animals instead is sure to be suspect in other ways.

Late in the Narnia series there is a montage of creation, showing how Aslan, the Christ figure, first drew them out from among ordinary animals and called them into being. They sing: “We hear and obey. We are awake. We love. We think. We speak. We know” — all things that would be impossible without their new awareness.

And Aslan, instructing them, says first and foremost that he gives them themselves. In one sense, the power to rise above your instinct is the power to be other than you are, to not be your “natural” self. But in a deeper sense, it is the power to be who you most are, to take responsibility for what you think and do and to guide yourself towards the better (or not).

Can elephants do that?

We know they undergo extensive education: babies from their whole doting families, newly fertile cows guided by the more experienced, lately independent bulls tagging along after their more magisterial superiors. In situations where these teaching opportunities are absent — babies orphaned or separated, cows giving birth alone in zoos, teenage males running rampant in places where all the older bulls have been shot for their tusks — their necessity is obvious. As good a guide as inborn instinct is in so many respects, this is one animal for which society, too, makes all the difference in the world.

While much of what it means to be a better elephant is conveyed by example — along with ear flaps, trunk movements, smell signals, and other forms of body language — elephants vocalize prodigiously as well, engaging in elaborate discussions as part of every activity. They have a vocal range of ten octaves (a piano has seven), and up to three-quarters of the sounds they produce are inaudible to human ears. Their infrasonic calls have been studied extensively by Katy Payne, a whale-call specialist who in 1984 found herself at the Portland Zoo observing elephants communicating “silently” through concrete walls. The “throbbing” or “shuddering” in the air reminded her of a bass line on an organ that descended past the point of hearing. In subsequent months at the zoo and years in the field, she recorded and deciphered many of these low frequencies with the help of spectrogram analysis and Joyce Poole, who had already learned to recognize dozens of the rumbles, hoots, trumpets, and whistles that are audible: “let’s go,” “I’m lost,” different referents to family and nonfamily members, and more. (Conversely, like other trainable animals, captive elephants have a minimal familiarity with human languages, recognizing many words spoken by their caretakers. Recently, an elephant named Koshik at a South Korean zoo even took it upon himself to learn to articulate human speech sounds: by sticking his trunk in his mouth, he can conform it to say hello, no, sit down, lie down, and good in Korean. In 1983, there were reports of an elephant in Kazakhstan named Batyr who could say “Batyr is good” in Russian and twenty other phrases, but they were not followed up on scientifically.) The work, tantalizing but in early stages yet, continues at the Elephant Listening Project.

Meanwhile, Caitlin O’Connell-Rodwell, originally an insect biologist, got involved when the Namibian government hired her to attack the perennial problem of keeping elephants from raiding crops. Fences, ditches, sirens, and border rows of chili peppers had all failed to protect local farmers’ livelihoods or were impracticable to maintain. O’Connell-Rodwell’s solution was to isolate a particular elephant alarm call out of a recording of layered vocalizations and rig it up to play back when they came too close. The reaction was astonishing: with none of the customary deliberation or signaling from a leader, they instantly flapped out their ears and whooshed away.

Her larger finding, however, recounted in her 2007 book The Elephant’s Secret Sense, was to prove that they communicate not only infrasonically but seismically — through waves in the ground. This radically expanded their known range of contact, indicating that they can keep tabs on who is where and what is going on by footfalls many miles away.

Elephant feet are padded with a kind of fat, similar to that found in aquatic mammals, that is ideal for acoustic transmission. (In fact, it was once used for candle oil, just like whale blubber.) Seismic waves traveling through the ground are picked up by the padding and transmitted up the foot and leg bones to the head, where smaller pockets of the same fat connect to the auditory system.

(Because of this enhanced pedestrian sensitivity, the feet are also especially susceptible to distress — sometimes, as Mark Shand writes in his 1999 book Travels on My Elephant, when an elephant goes rogue, it is because a stick that it was using to clean between its toes has splintered off and lodged in out of reach. And severe elephant foot problems are depressingly common in zoos and other captive situations, where the animals must stand on concrete so much of the time instead of walking long distances over soft dirt and vegetation.)

O’Connell-Rodwell’s discovery made immediate sense of any number of strange elephant phenomena: their habit of “synchronized freezing,” falling still together to “listen” on tiptoe to an incoming signal; their disturbed behavior just before a major seismic event such as an earthquake or tsunami; the way that bulls, who don’t casually intrude on matriarchal groups, would seem to know from far away exactly when a cow was going into estrus and head straight for her. Long before Payne and O’Connell-Rodwell’s work, when early ethologists were just getting the lay of the land and using radio tracking to monitor elephant movements, they were baffled by the elephants’ ability to seemingly coordinate across long distances and change course near-simultaneously, regardless of wind direction (and thus scent) or any other explanation they could think of. “We didn’t mention ESP openly,” said Iain Douglas-Hamilton, but “some of us were ready to entertain the idea that these animals were sending bloody mind waves to each other.”

With hard work and careful observation, a better explanation was eventually forthcoming, as there may one day be for other elephant-related phenomena that seem a little spooky. Many people, for instance, report a kind of sixth sense about when an elephant is in the area, one they cannot actually perceive in any identifiable way but seem almost never to be wrong about. Poole describes it as “a vibrancy in the air, a certain warmth,” or by contrast “a stillness, an emptiness” in the landscape when elephants are absent. Conceivably, this elephant radar may be produced by the talking tremors, felt viscerally rather than audibly — but less obviously explicable is Poole’s similar sense of whether she is about to find a carcass with ivory attached.

Lyall Watson’s fascinating 2002 book Elephantoms is largely devoted to exploring this sort of not-intrinsically-unreasonable event that verges on the uncanny. One of his more straightforward stories concerns an incident witnessed by a ranger in Addo Park, South Africa, home to a line of elephants with special historical reasons to distrust human beings. An effort to repair a fence had resulted in a mother and baby being stranded on opposite sides of it. Becoming very agitated as the workers approached, the ranger said, the cow “stopped, put her trunk through the cables to calm the calf and seemed to be thinking about her next move.” He said he could not prove what happened next, nor did the other rangers believe him, but this is what he saw:

She talked to that kid. She told him exactly what to do, and without any further fuss, he did. He turned out away from her and the fence and went into the deep shade of a tree twenty yards away, where he stood motionless, becoming virtually invisible. I knew exactly where he was, but could hardly find him again when I looked away. I saw her rush down to the gap and out onto the road, and as the truck appeared, she raised a huge cloud of dust, stamping and blowing, making short charges at the vehicle, frightening the crew sufficiently to get them to back off and go away…. And when the noise and confusion was at its height, the calf in camouflage made his move. He sidled over to the fence, slipped quietly through the gap, and went over to wait in the cover of the succulent forest.

I was certain then that the cow’s entire performance had been a brilliant diversion, beautifully executed, for as soon as she was sure he had made good his escape, she ignored the truck and its occupants and turned her back, sashaying in satisfaction back to join her calf in the safety of the park.

Evidently it is not uncommon for those who spend their time out monitoring or at least mingling with wildlife to witness occurrences that go beyond conventional assumptions about what animals can know or do. When “elephant whisperer” Lawrence Anthony died in 2012, the two herds of traumatized rogue elephants he had saved and resocialized crossed the vast South African game reserve where they lived, apparently to pay their last respects. The elephants had not been anywhere near the house for a year and a half prior, Anthony’s son reported, and the trek across the park could take a day, but within hours of his death they all showed up.

Payne writes of a conversation she had with a senior scout from Ntaba Mangwe park in which she asked him how he speaks of events that seem to be outside normal experience. “YOU JUST TELL WHAT HAPPENED,” he surprised her with a shout and burning stare. “YOU JUST TELL WHAT YOU SAW!”

“You must simply tell what happened,” he repeated quietly as she sat there in shock. “Only God knows what it means.”

Unpacking this remarkable exchange yields several items of note. First, there is the dynamic presence of the unknown in daily life. Second, there is the question of what to do about it. Because it is unknown does not mean that it is necessarily unknowable — nor that it isn’t. The choice to tell about it represents a hopeful effort that it might be understood, though not a presumptive one: there is no undue effort to explain, to impose some kind of theory on it, but an openness to whatever it might reveal. But finally, on the optimistic side of understanding, there is a reminder of the awesome significance of language in the urging to tell what happened. What could be more crucial in the search for truth than this ability to translate individual experience into common comprehensibility? You just tell what happened, and someone else will hear it.

The website LettersOfNote.com is a wonderful, weird archive of real epistles between all kinds of people in all times and places. A striking proportion of them, however, seem to be letters from former slaves to their erstwhile masters — some forgiving and generous, some righteously sly, a few burning with revenge, all at varying degrees of written literacy, but uniformly powerful for this reason: they say, I have a mind. I have an independent soul that never once belonged to you although my labor and all the circumstances of my life unjustly did. You found it convenient to believe that I was not a thinking, feeling person just like you — no doubt supported by elaborate rationalizations from the whole world around us which ought to have known better — but you cannot deny this anymore, because here I am, free and awake. I love. I think. I speak. I know.

It must be emphasized that the direct comparison here is not from the harm and injustice of animal captivity to those of human slavery, but in the ability to command the attention of someone in power who does not want to acknowledge them at all. To the extent that elephants and other animals have thoughts and memories and feelings and experiences that they are capable of expressing in their own tongue, what a disadvantage it is to them that we have not cracked that code. Our failure to understand them means that there is no way we can truly assess the limits of their abilities or say for sure what they are not saying, and makes it easy to ignore their validity for anyone with reason to. No animal is going to come forward with a written missive in a humanly comprehensible language detailing wrongs or simply proving in our own terms the scope of its existence — that, at least, is an ability that is distinctly ours. But if they could, they would have a lot to tell.

When I saw this place, I told her that there’d be no more chains. She’s free now. And I just thought about, I don’t know who was the first to put a chain on her, but I’m glad to know that I was the last to take it off. She’s free at last. I’ll miss you, Shirley. My big girl.