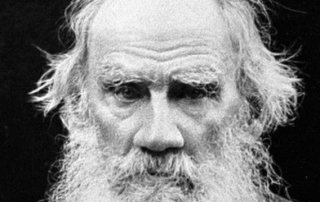

There is much in Leo Tolstoy’s frightening and brilliant story The Death of Ivan Ilyich that is relevant to my previous post about CPR in the hospital. The novella concerns an upper-middle-class judge, Ivan Ilyich, his rise within the Russian legal system, and his subsequent death. Tolstoy describes Ilyich’s unremarkable and vapid professional and personal life — his accomplishments are not long-lasting and he despises his wife and cares little for his family — and contrasts this profoundly with Ilyich’s lingering march toward death.

I’d like to focus on two of the interesting points that Tolstoy makes about death. First, death itself is only a concern for the dying, while others are insouciant, opportunistic, or burdened by the obligation of dealing with a friend’s passing. Upon hearing of his death, Ilyich’s legal colleagues first thought “of the changes and promotions it might occasion among themselves or their acquaintances.” And one friend complains about traveling to the funeral: “…but they live so terribly far away.” Perhaps even more disturbing, “the mere fact of the death of a near acquaintance aroused, as usual, in all who heard of it the complacent feeling that, ‘it is he who is dead and not I.’ Each one thought or felt, ‘Well, he’s dead but I’m alive!’” Again, Tolstoy emphasizes the disturbing frustrations Ivan’s friends felt: “But the more intimate of Ivan Ilyich’s acquaintances, his so-called friends, could not help thinking also that they would now have to fulfill the very tiresome demands of propriety by attending the funeral service and paying a visit of condolence to the widow.” This haunting view of human nature should make us all cringe — how lonely death is and how cruel is the human response to it!

On that night I helped perform CPR, were those of us surrounding the dying patient in the hospital feeling as insouciant or feeling as burdened as Ilyich’s friends? Though Tolstoy’s dark view on such matters may hold true in some cases, I think that experience on the night shift was completely antithetical to Tolstoy’s understanding. In the hospital room, the feeling was not one of an obligation or burden. The attending physician kept CPR going because he wanted to give this young woman every shot at coming back to life. Then, he hurriedly tried to get in touch with the patient’s family, trying cellular numbers, home numbers, and even work numbers, to tell them what had happened. He covered up her chest with a blanket out of respect for her. And when he called the time of death, the palpable silence in the room was telling. There were no words to account for this process. In some ways, silence was the appropriate response. Nobody complained about other chores they had to do, or about the paperwork that had to be done or how much time they spent trying to resuscitate this patient.

Tolstoy also writes about the experience of dying, which makes up a large part of the novella. Ilyich sees death on the horizon and his inexorable march towards it. “In the depth of his heart he knew he was dying, but not only was he not accustomed to the thought, he simply did not and could not grasp it.” Ilyich attempts desperately to ignore death: “The pain did not grow less, but Ivan Ilyich made efforts to force himself to think he was better.” Towards the end of this process, Tolstoy describes Ilyich’s reactions: “[He] wept like a child. He wept on account of his helplessness, his terrible loneliness, the cruelty of man, the cruelty of God, and the absence of God. ‘Why hast Thou done all this? Why hast Thou brought me here? Why, why dost Thou torment me so terribly?’ He did not expect an answer and yet wept because there was no answer and could be none.” This is compounded further by Ilyich’s regrets about the life he led: “And the further he departed from childhood and the nearer he came to the present the more worthless and doubtful were the joys.” These moving passages summarize the dreadfulness of Ilyich’s confrontation as Tolstoy drags the reader through this horrific scene. During the last few days, Ilyich screams continuously, which is “so terrible that one could not hear it through two closed doors without horror.” And it is only when Ilyich admits to himself that his family would be better off with him dead (“It will be better for them when I die”) instead of watching him die, that he is freed from his pain and “in place of death there was light.”

Interestingly, Ilyich initially approaches his final minutes the way those who do CPR approach death, the way Dylan Thomas wanted his father to approach death, and the way so many people encouraged Christopher Hitchens to approach his cancer — with rage and a desire to do battle. Ilyich clings to false hope and attempts to confront death. In the end, though, he mitigates his suffering and the suffering of others only by submitting peacefully to his inevitable passing. Does this mean one must always allow death its victory, and must even pursue death, through means like euthanasia, when one is in intense pain? No, I think Tolstoy’s point is far more nuanced than that. Ilyich does not commit a form of suicide; he merely accepts his fate, which is when his pain and fear disperse. A good analogy might be the kind of care the field of medicine provides to terminally ill patients. We now attempt to provide comfort and care for the dying through hospices, institutions which give nursing care and pain medications to those with terminal illnesses in order to make their passing a comfortable rather than a painful struggle. This method is increasingly common and improves patients’ quality of life at the end in certain instances. (I will write more about hospices and issues related to end-of-life care in coming posts.) And this does not invalidate the option for a fight when it is appropriate and when something can and ought to be done. For those other than Ivan Ilyich, like the woman in the hospital on that night, there is still the hope of being saved. This option we must pursue no matter how difficult the pursuit is, so that, to borrow from Tolstoy, in place of death there is life.