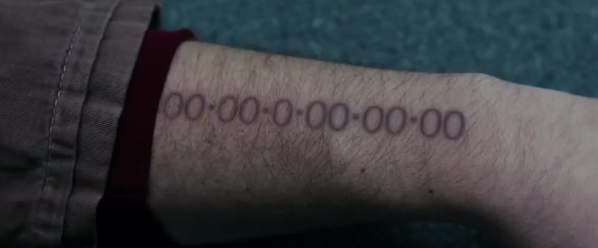

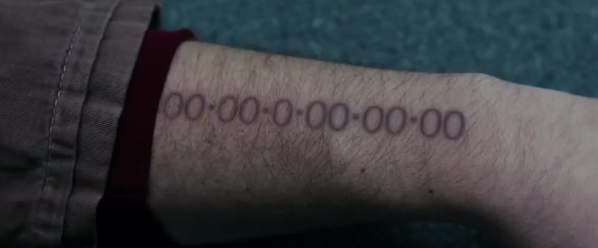

I just recently got around to seeing Andrew Niccol’s 2011 movie In Time. In the dystopian world the film depicts, people are genetically engineered to stop aging at 25, but they will die by 26 unless they can earn enough time to keep living, with this living-time also serving as currency. Why and how this system was established are never explicitly spelled out; indeed, in the world of the movie, it seems as though things had ever been thus. No one expresses any nostalgia for a time before time was currency, and however resentful many of the characters may be of the inequality and injustice of the distribution of time, no one ever thinks to challenge the actual use of the anti-aging technology that underlies the whole system. As Emily Beitiks’s review over on the CGS website notes, the film’s central message is a critique of economic inequalities in our own time. A shadowy cartel of bankers controls the world’s time, with its members preserving their opulent lifestyle by oppressing the poor with exorbitant interest rates.

But beyond the movie’s cliché-riddled Robin-Hood steal-from-the-rich narrative, the fact that

living-time was used as a currency gave the movie a few more thoughtful moments. Also, the theme of population control — one of the

dark undercurrents running through such movements and ideologies as social Darwinism, eugenics, and neo-Malthusian environmentalism — was strongly implied throughout the film. As the despairing time-rich Henry Hamilton tells the movie’s protagonist, Will Salas:

For a few to be immortal, many must die…. Everyone can’t live forever; where would we put them?… The cost of living keeps rising to make sure people keep dying. How else could there be men with a million years while most live day to day? But the truth is, there’s more than enough. No one has to die before their time.

Hamilton, who is 105 years old, has grown tired with life, goes on to tell Will that “the day comes when you’ve had enough. Your mind can be spent even though your body’s not. We want to die. We need to.” Hamilton’s message has clear implications for those interested in radically extending the human lifespan: he reports that some people grow tired of living forever. The idea is not fully fleshed out in the film, and even in Hamilton’s own case we are given reasons to believe that it is guilt over the inequalities of society rather than mere exhaustion with living that drives him to despair. After all, Hamilton doesn’t kill himself in his own wealthy neighborhood; rather, he travels to the slums, spending his time-currency buying drinks for the destitute people his class had long oppressed, in a neighborhood where people with “too much time on their hands” are regularly robbed and murdered by gangsters. Just as these gangsters, called “Minutemen,” are about to “clean his clock” (sorry, but the movie is ham-handed with the punning), Will rescues the seemingly naïve rich man, taking him to an abandoned warehouse where they spend the night sitting in uncomfortable chairs, and Henry explains his intention to die to Will. The next morning, while Will is still sleeping, Henry gives our hero almost all of his time-currency. Hamilton leaves himself just enough time to walk to a nearby bridge and write as a suicide note what is perhaps the only decent play on words in the movie: “don’t waste my time.”

The characters in In Time are largely defined in terms of what their time and mortality mean to them. The strength of the film is the way it explores the meaning of mortality, poverty and oppression among the different classes. Unfortunately, this emphasis on the effect of social class leads the characters to be perhaps too sharply defined in terms of class roles — there’s the tired Robin Hood narrative again — making the film’s message about social justice feel heavy-handed and simplistic.

The poor, who wake up in the morning knowing that they will need to earn time-currency just to survive the day, are willing to take the kinds of risks necessary to really live life to the fullest — and despite their poverty and desperation, many of them show admirable generosity. In contrast, the rich, who could live forever if they “don’t do anything foolish,” are far more anxious about death. They are surrounded by bodyguards, they seem to live only indoors, and they never even take advantage of their beautiful beachfront properties by risking their lives with a swim in the water. Near the film’s climax, the disaffected daughter of a super-rich banker tells her father, “We’re not meant to live like this. We’re not meant to live forever. Although I do wonder, Father, if you’ve ever lived a day in your life.” Living in constant anxiety about death, and attempting to exert rational control over all the circumstances of life in order to unnaturally prolong it, leaves the immortal lives of the time-rich hollow and joyless.

In the movie, the rational control that the rich exert goes so far as draconian population control measures that kill millions of poor people. In the real world, without the time-as-currency conceit, the risk-averse people of today and tomorrow might well find themselves trying to secure their continued existence by controlling their circumstances in other, less evil ways that nonetheless may leave them leading empty, less fulfilling lives. As our ever-insightful

New Atlantis colleague

Peter Lawler imagines:

We might be looking forward to a future with people blessed by technology with indefinite longevity obsessing over their lack of immortality. Death, having become much less obviously necessary and much more seemingly accidental, might consume our lives. We’ll knock ourselves out like never before in accident-avoidance strategies — maybe spending our lives in in lead houses communicating with our virtual (and so non-threatening) friends with the most advanced forms of social media.

Niccol delivers a similar message with

In Time, reflecting on how our technologically mediated mortality profoundly shapes our lives.

[Images © 20th Century Fox]

> Living in constant anxiety about death, and attempting to exert rational control over all the circumstances of life in order to unnaturally prolong it, leaves the immortal lives of the time-rich hollow and joyless.

That goes to show why authors of fictional stories about radical life extension need to study real psychology instead of recycling unscientific folk psychology. According to Terror Management Theory in psychology, which has experimental support, we already live in "constant anxiety about death" every day of our lives. Indeed, you could interpret the ordinary "human condition" as a kind of chronic stress disorder which starts when we learn of our mortality in childhood:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terror_management_theory

There are many religious people who do think that we are meant to live forever.

"That goes to show why authors of fictional stories about radical life extension need to study real psychology instead of recycling unscientific folk psychology…. we already live in "constant anxiety about death" every day of our lives."

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evel_Knievel

Sure, maybe you could explain his daredevilry as a way of coping with anxiety about death in some roundabout way, but even without going through any experiments or peer review we can say that he didn't act as anxiously about death as most people.

So I don't think Niccol is being unrealistic when he says that some people might act more or less anxiously about death than other people.

Thank you though, Mark, for telling me about that Terror Management Theory; I hadn't heard of it before, and it actually does sound like it has some interesting ideas.

Joseph – that is very true, lots of religious folk believe that eternal life is part of the story. But to take the example of Christianity, the Good News is that we don't need to be anxious about death, even to the point that anxiety about death seems to be thought of as something to avoid: "Very truly I tell you, unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds. Anyone who loves their life will lose it, while anyone who hates their life in this world will keep it for eternal life." (John 12:24-25)

And to be clear, the character in the movie who said that we are not meant to live forever was not religious. Religion was actually conspicuously absent from this movie about mortality, now that I think of it.