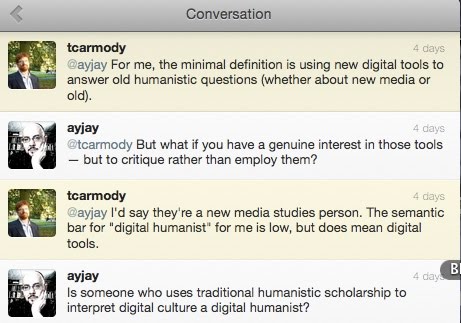

So I was having this conversation on Twitter the other day. I asked the question because I was thinking about Marshall McLuhan, about whom I am writing an essay that will (God willing) appear in a future issue of The New Atlantis: I was wondering whether it would make sense to call McLuhan a digital humanist. If Tim is right in his response, and I think he probably is, then McLuhan is actually the opposite of a digital humanist. If the digital humanist uses new tools to analyze old texts (and other media), McLuhan used the old tools of (a) early modern rhetorical analysis and (b) modernist literature and literary criticism to analyze new media. It was McLuhan’s core conviction that if you want to understand contemporary audio and visual media, from radio to billboards to television programs to comic strips — McLuhan was especially fascinated and appalled by Dagwood Bumstead — your best tools derived from historians of ideas (Eric Havelock), literary historians (John Hollander), anthropologists and ethnographers (Mircea Eliade), and contemporary novelists and poets (Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, James Joyce).

What the world needs now, to coin a phrase, is someone with McLuhan’s commitment to humanistic scholarship who is also geeky enough to know the world of code from the inside.

(UPDATE: I forgot to say that you need to read those tweets from bottom to top. I should have Storified them before posting. Sorry.)

Text Patterns

February 25, 2011

Say one already knows code from the inside. How would one get the full set of tools for and commitment to humanistic scholarship?

Interesting question, Katie. I suppose the answer would depend on what you wanted to do with that knowledge. Formal education, with its accompanying credentials, is the only current path to making a living as a scholar in the humanities. But for those who are interested in humanistic learning for its own sake, it would be good to start by acquiring an historical awareness of what humane learning had been over the centuries. Anthony Grafton is a wonderful guide to these matters. See my review of his book Worlds Made of Words, and see his brilliant essay-review on an interesting recent book by Louis Menand.

After that: read. Read lots. And learn Latin.

Thanks Dr. Jacobs, I will look into that book and article.

McLuhan didn't really have any "digital tools" available to him, so it would be a bit of a distortion to say he was the "opposite" of a digital humanist (using Carmody's definition), which implies a rejection of those tools. If you look at a book like "The Medium Is the Massage," you could even make an argument that McLuhan was striving to achieve the effect of "digital tools" before those tools had been invented.

Nick

Nick, I mean that McLuhan's method — devoted as it avowedly was to the conservation of a Gutenbergian world — is functionally opposite to digital humanism, that is, working from the other end of the street, so to speak. I'm agnostic about what McLuhan would have done had digital tools been available to him; I'm just talking about what he did do.

Along similar lines, Zizek has observed somewhere that 19th century novels (Dickens, Madame Bovary) anticipated cinematic techniques — a certain mode of perception was struggling to find a means of articulation. Likewise, there is arguably a "digital" quality to the associative logic of McLuhan's writings, as if the logic could be best conveyed within a digital environment, but struggled to assert itself in print.

Mike

Yes, you're on to something. This is a question I've been thinking about for some time.

While Mcluhan was writing about new oral/acoustic communications mediums, he articulated his ideas through the written word.

Likewise, while this new media was turning the West into a tribal village, Mcluhan noted this trajectory through the Greek Narcissus, not through a new set of neo-tribal Gods and myths.

I've always wondered about the value in this. Why did Mcluhan not abandon the Humanities in favor of a post-Humanities?