I’m going to disagree, a bit, in a way, with Robert George’s Advice to Young Scholars:

Although it is natural and, in itself, good to desire and even seek affirmation, do not fall in love with applause. It is a drug. When you get some of it, you crave more. It can easily deflect you from your mission and vocation. In the end, what matters is not winning approval or gaining celebrity. Your mission and vocation is to seek the truth and to speak the truth as God gives you to grasp it.

There is a particular danger for those who dissent from the reigning orthodoxies of a prevailing intellectual culture. You may be tempted to suppose that your willingness to defy the career-making (and potential career-breaking) mandarins of elite opinion immunizes you from addiction to affirmation and applause and guarantees your personal authenticity and intellectual integrity. It doesn’t. We are all vulnerable to the drug. The vulnerability never completely disappears. And the drug is toxic to the activity of thinking (and thus to the cause of truth-seeking).

To me, the reality of this temptation, no less than any other temptation, should keep us mindful of the need constantly to tend the garden of one’s interior life. If anything can immunize us against the temptation to love applause above truth, it is prayer.

There is obvious and important truth in this, for the Christian scholar, and yet I think George has phrased the matter in terms that are too individualistic. (I doubt that George would disagree with any of what I’m about to present, and would probably say that it is implicit in what he wrote. But I think it needs to be more explicit.)

The prayerfulness that George rightly emphasizes needs to be not just private prayer — which is what at least some of his readers will think he means — but communal prayer, within a body of faithful believers. I agree that my “vocation is to seek the truth and to speak the truth as God gives you to grasp it,” but I need to test my own self-understanding against that of the larger body. I need people to whom I am accountable to tell me when they think my discernment is flawed. They won’t always be right; but without them I am sure to be usually, if not invariably, wrong.

I think we should keep that point in mind when we reflect on George’s absolutely vital point about the dangers of congratulating ourselves on our “dissent from the reigning orthodoxies”; even when we do so dissent we can still, without realizing it, crave “applause more than truth.” Jamie Smith recently articulated a very sharp version of this point:

Those “courageous” progressives don’t really value the opinions or affirmations of conservative evangelicalism anyway. What they really value, long for, and try to curry is the favor of “the Enlightened” — whether that’s the mainstream academy or the progressive chattering class who police our cultural mores of tolerance. Sure, these “courageous” progressives will take fire from conservative evangelicals —but that’s not a loss or sacrifice for them. Indeed, their own self-understanding is fueled by such criticism. In other words, these stands don’t take “courage” at all; they don’t stand to lose anything with those they truly value.

Similarly, “courageous” conservatives who “stand up” to the progressive academy aren’t putting much at risk because that’s not where they look for validation and it’s not where their professional identities are invested. They are usually “populists” (in a fairly technical sense of the word) whose professional lives are much more closely tethered to the church and popular opinion. And in those sectors, “standing up to” the academy isn’t a risk at all–it’s a way to win praise. When your so-called contrarian stands win favor from those you value most…well, it’s hard to see how “courage” applies.

To this I reply with a warm Yes — and also an Ouch, because I’m sure I have done just this: patted myself on the back for my “courage” in standing up to people whose approval I didn’t want anyway. The key point is: We always want someone’s applause, someone’s approval.

The question is: Whose? Here I want to go back to my recent post on the Righteous Mind and the Inner Ring, and C. S. Lewis’s distinction between Inner Rings, which draw people in to their destruction, and communities which offer the kind of genuine membership that contributes to our flourishing. Lewis’s best treatment of these issues is his novel That Hideous Strength, which is flawed in many ways (I think) but absolutely brilliant on this point.

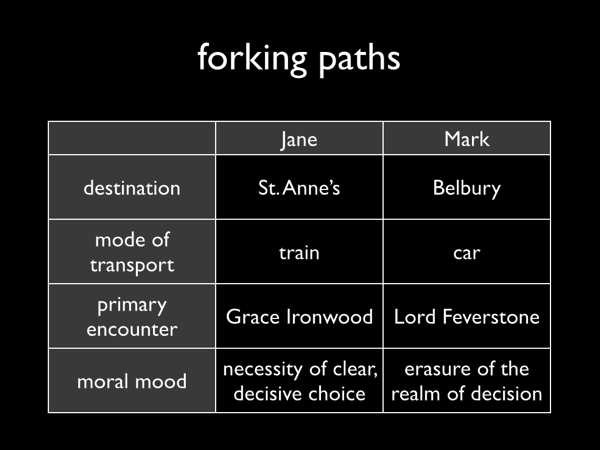

The image at the top of this post, and the one that’s about to follow, come from a talk that I’ve given a couple of times on this theme. In THS Lewis portrays with great skill the rhetorical differences, which are also moral differences, between Mark Studdock’s recruitment into N.I.C.E. and Jane Studdock’s invitation to join the company at St. Anne’s.

Jane, like Lewis himself, wants to be left alone, and resists incorporation into any social body. Mark craves affirmation — applause — and is undiscerning about who it comes from. Jane has to learn the value of belonging to people who are trustworthy and want her to flourish; Mark has to find the courage to resist being assimilated by a voracious social machine that wants to consume him. Their paths fork; then converge.

I think moral maturity for all of us involves learning what our temptations are. Do we (falsely) think we can go it alone? Are we tempted to go along to get along? Do we even understand what groups we want to belong to — whose applause we desire — and why? I can’t imagine anybody to whom these questions are not relevant, but they have a particular importance for scholars, because scholarship is something that we learn within really powerful socializing institutions. (I don’t know of any institution that socializes more thoroughly than graduate school.)

Simply to give in to these forces is unwise; to be completely independent of them is impossible. This is why I have always insisted on the importance for Christian scholars of serious commitment to a church community: by participating in a different body, with different priorities and participants, you are better able to put the demands of the scholarly world into proper perspective. You don’t escape them or ignore them or rise triumphantly above them; but you can learn to give them the conditional and limited allegiance they deserve.